Your Planets

Portraits of the Planets

Aspects between Planets

The planetary ages

The planetary families

Planets in Signs

The Planets in comics

The nature of astrological effects is primarily conjectural, stochastic and chaotic. There is therefore no mechanical astrological determinism of which a statistical study could show, and not demonstrate, the probability or the improbability. This fact has not stopped supporters and opponents of astrology from indulging in it for better (rarely) and worse (almost always). However, serious statistical studies could highlight and detect some of the most salient and therefore most visible astrological effects. But these have never been made, although all the elements are in place for them to be made. For daring researchers, a vast unknown territory therefore remains to be explored, knowing that it would be limited to the tip of the astrological iceberg, of which around 90%, by spinning this icy metaphor, would therefore remain beyond the reach of any statistics…

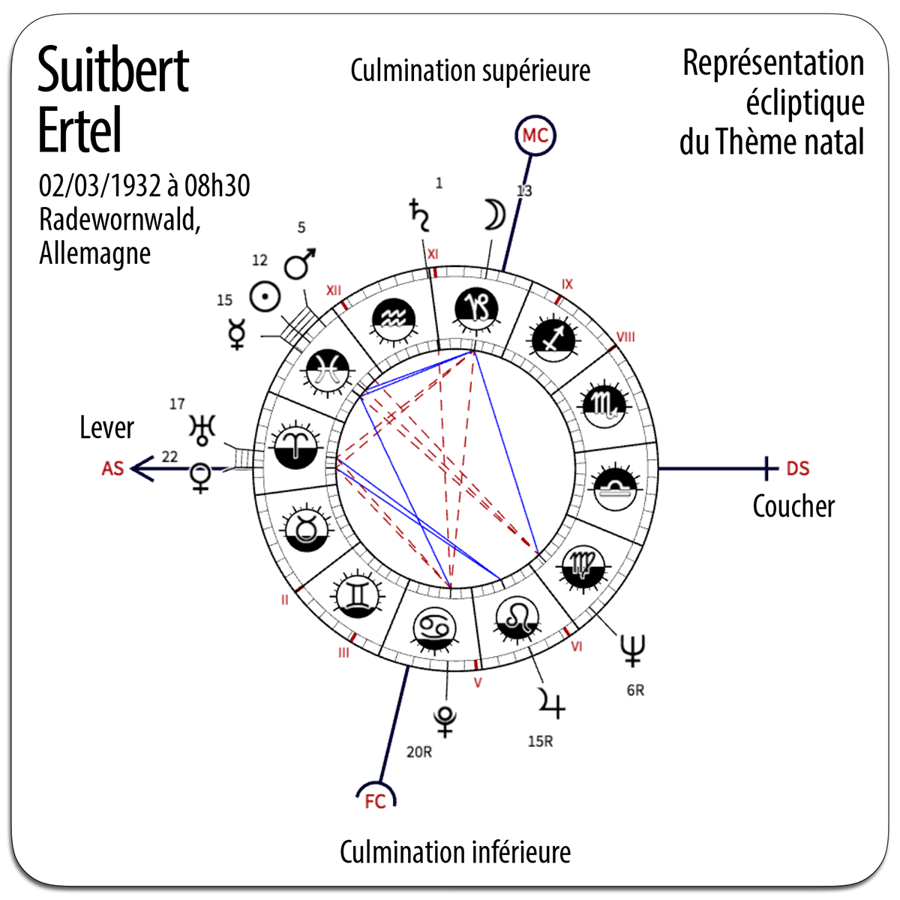

In 1992, Suitbert Ertel published in the Skeptical Inquirer a study confirming the statistical reality of the “Mars effect” and who more revealed a very interesting new element. She has indeed shown that the “Mars effect” was independent of all astronomical variations such as the distance between Mars and Earth, its apparent size and magnitude, its declination and right ascension, its orbital position and distance from the Sun, its position behind the Sun, and that finally it did not vary according to the terrestrial geomagnetic activity. From this surprising discovery, only two conclusions could be drawn: either the “Mars effect” had no physical basis, or it was subject to as yet unknown physical laws and properties – which is the most probable hypothesis. So the mystery deepened.

In the same article, Suitbert Ertel confirmed that his replications of studies on the correlations between “character traits” and planets had shown that the statistics of Michel Gauquelin on this subject, then after his death those of Françoise, suffered from too great a confirmation bias for their positive results to be validated. But Suitbert Ertel’s replications involved extremely small samples (just over 100 natal charts), which could only have made their relevance uncertain. He used to challenge these results the same method as Michel Gauquelin, exclusively based on the lexical counting of biographies. He nevertheless asserted that these confirmation biases were unmistakable: “Gauquelin, as a feature extractor, was greatly influenced by his knowledge of the sector positions of the people on whose biographies he worked.” Michel Gauquelin died in 1991 before he had any further argument against these conclusions. It was also her own death in 2007 that prevented Françoise Gauquelin from objecting to a new replication by Suitbert Ertel made in the early 2000s and which had produced the same results.

These confirmation biases, which appeared late in the Gauquelins’ studies, show above all that after about 40 years of research, they were sufficiently convinced of the relevance of their statistics that they then began to behave like astrologers who knew in advance, rightly or wrongly, what they had to find out. In this sense they made a serious mistake: they should have changed their method and moved from frequentist statistics to Bayesian ones. Nevertheless, it can be objected to Suitbert Ertel that the significant correlations between professional celebrities and the positions of certain planets in the key sectors of the local sphere were implicitly based on an astro-psychological hypothesis.

In his first book The influence of the stars, Michel Gauquelin vigorously denied having a priori included characterological parameters in his initial research hypothesis. He claimed to have chosen the professions he selected only because they had a lasting character, that their goals were precise and that as such they strongly committed those who dedicated themselves to them. But when it came to drawing conclusions from his results, he did not hesitate to appeal to purely psychological notions.

Here is what he wrote about it: “There appears each time between these groups […] a common fundamental particularity, and this particularity is described in terms of character” (emphasis added). He then describes these character traits: “Mars: energy, struggle, concrete activity (athletes, doctors, soldiers); Jupiter: the desire to represent, the spirit turned towards the external and public aspect of things (actors, soldiers, deputies); Saturn: the desire to meditate, to reflect, the mind turned towards the deeper aspect of things (scholars, priests).” However, we must not overlook the fact that Michel Gauquelin was an astrologer in his youth, that he was well acquainted with traditional astrological literature and that he had practiced astrology. He therefore could not ignore that the astrological literature attributed to each planet a propensity to exercise certain professions according to the characterological dispositions that these preferentially required. It was therefore at least partly guided by this hypothesis that he used the criterion of professions for his first astro-statistics. It is remarkable that none of the critics detracting from his work ever mentioned this fact. But no doubt you have to be a convinced astrologer to be able to notice it.

No statistical research can do without an initial hypothesis, however eccentric or heretical it may be. There can therefore be no question of criticizing the fact that Michel Gauquelin chose this one rather than another. He explains this by writing that what he wanted to establish “examining such professionally related groups was […] an inherent and enduring characteristic of Man. Enough durable and characteristic to manage to manifest itself in an objective and exterior concept like the profession, which would only be its approximate and moving reflection. We therefore understand to what extent it was necessary for us to seek the most stable professions through the ages; and on the other hand, this explains why we have chosen the most representative individuals of these professions. […] Whatever interpretation we attempt to give to the results obtained, the profession will have been only a pretext for us to reveal simple, stable factors inherent in men of all backgrounds and of all periods.”

Stated in this way, the professional criterion seems to be a sensible choice and apparently devoid of any a priori, whether in a favorable or unfavorable sense to astrology. This is at least what Gauquelin wants us to believe. However, we have seen that this was not the case: this hypothesis was in fact very strongly oriented. It was in the sense that he knew from the outset that each profession corresponds for astrology to a privileged planet or vice versa, that each planet is associated with professions in accordance with the meanings and “character traits” granted to him. He therefore does not venture into unfamiliar territory. He cannot be blamed for this either: this type of hypothesis is quite common in the field of research, whether statistical or otherwise.

On the other hand, it is much less common to know in advance what positive or negative results this statistical research will most likely lead to. And it is even less common for a researcher to give himself the opportunity to be able to have it both ways, that is to say to have the possibility of declaring himself very satisfied with the results of his research, than these confirm or invalidate his initial hypothesis, considering that in both cases he was right. However, in general, an experienced researcher has no time to waste testing weak hypotheses which he knows are very likely to be almost certainly invalidated. He prefers to test strong hypotheses, which he considers valid given his expertise, with the hope but not the certainty that they will be confirmed. These strong hypotheses can be positive (the researcher then tests for a possible confirmation) or negative (in this case, he tests an invalidation that he considers probable). He does not test both a positive and a negative hypothesis and if he does, he takes great care not to mix the two, under penalty of not being able to obtain any significant result and consequently of not being able to draw any conclusion from his study.

This is not how things happened in the case of Michel Gauquelin. He certainly played heads or tails, but by betting on both the back and the front of the coin he was tossing into the statistical maquis. From this probable initial bias, we can infer two hypotheses as to the objective he pursued by embarking on his research. Either he intended to demonstrate the falsity of astrological assertions in relation to character and profession, or he thought he had found with the professional field a so-called ground “neutral” to at least partially confirm these. So he made a bet that seemed risky, since he couldn’t a priori be certain of the results he would obtain. But in both cases he played a winner every time from a personal point of view, given that he never hid that from adolescence he intended to make a name for himself, become a legend and reach the celebrity in the field of astrology.

▶ In the first as in the second case, he knew from the start that by confronting the planetary positions in the local sphere with the astrological assertions concerning the professional orientations, he left winning given the very strong correlation between the two. Heads, he won a celebrity destructive of astrological assertions and tails, he won another by becoming the herald-hero of a neo-astrology. The only thing he couldn’t know for sure right away was which way the coin he flipped would land. It just so happened that she fell on the face side, the side that made him a “neo-astrologer”. He was obviously satisfied with it, given that in this perspective he could continue on his momentum since a avenue of future research opened before him. The tails spin would probably have suited him less, in the sense that it quickly put an end to the same research and he would then have had to devote his life to something other than astrology.

▶ If we adopt this point of view, the bet he made did not put him at risk. If he invalidated the traditional astrological assertions by rigorous statistical investigations, he became the first to have finally scientifically struck down the astrological dragon, and as such he was certain to build a reputation. If, on the contrary, it confirmed, even if only partially, the same astrological assertions relating to “character traits” and to the professions that suit them, Michel Gauquelin became the first to have established as a statistical fact the existence of a significant correlation between the stars and men, and could claim recognition and scientific glory. It is very likely that this is the game he played very skillfully, and since he could not lose, he gained the astrological fame to which he aspired.

▶ This very personal and very probable motivation is not reprehensible as such. The various subjective motivations of the discoverers matter little when their small or large discoveries are objectively recorded. Only the results obtained count.

The fact remains that as soon as his astro-statistics produced their first results, Michel Gauquelin hastened to draw astro-psychological conclusions from them by drawing up a characterological profile for each profession, which was the only possible explanation. of the results obtained, and which resembled in all respects the profiles that can be found in astrology textbooks, the content of which he had known very well since his youth.

Of this fundamental characteristic of the initial hypothesis, Suitbert Ertel did not take into account in his refutation the confirmation biases about the “character traits” associated by the Gauquelins with the planets, which is a considerable blindness on his part. In all his statistical counter-surveys, Suitbert Ertel has always acted as if he considered the “character traits” as an independent variable of Michel Gauquelin’s starting hypothesis, which he could as such treat and test in isolation. But we have seen that Ertel was wrong. It is not an independent variable. The “character traits” lie at the very heart of Gauquelin’s hypothetical device. Without them, his astro-statistics are reduced to the discovery of a correlation between professions, stars and human beings, which nothing connects except the fact that the significant deviation from the expected average on which it is based does not is not a coincidence. No rational interpretation of the results is possible if we do not operate the junction between the trades and the planets by the mediation of “character traits”.

By considering this mediation only as an independent variable that could be neglected, and of which he wrongly believed that he had tested the statistical invalidity, Suitbert Ertel could only have one conception of the “Mars effect”. And it is precisely this that he has always developed: that of a mysterious and irrational effect, indubitable but inexplicable, associating stars and professions for an unknown reason, and which would strangely only concern populations of “champions” professionals, that is to say a tiny part of humanity. This is a delusional conception of Gauquelin astro-statistics. And what explains this delusional non-interpretation is nothing other than the fact that he considers the “character traits” as an independent variable, which they are not. Which is curious to say the least from Suitbert Ertel, Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of Göttingen.

After having accompanied them for a long time in their studies, of which he was always a critical support, Suitbert Ertel presented himself after their death as the successor of the Gauquelins and the continuator of their research. In a sense, this was not a usurpation, since he did not question the validity of the part of them relating only to professions. But he has otherwise, not considering the “character traits” than as an independent variable whose inanity he believed he had experimentally demonstrated, always carefully avoided and criticized the slippage of these astro-statistics towards some form of “neo-astrology” whether it be. Unlike the Gauquelins, he considered them a kind of paranormal phenomenon of an indeterminate nature and foreign to human psychological functioning. Which was not at all the conception that the Gauquelins had of it. From this point of view, the studies of Suitbert Ertel suffered from what could be called a “disconfirmation bias”, in that they were motivated by the systematic contestation of “character traits”.

The major error of the Gauquelins in their decision to test the hypothesis of “character traits” associated directly with the planets, without going through the professions, was not to change the method so as not to be suspected of confirmation bias. They should have made a 180° methodological shift, this time starting from the hypothesis that there was a correlation between certain professions and certain characterological inclinations, and that they were therefore legitimately justified in making new statistics based on another criterion than that of professions, that is to say moving from frequentist to Bayesian statistics. Of course they would then have evolved on a fuzzy and complex astro-psychological terrain (which is also the case for all the statistics about psychological facts). Indeed, if an individual can be mono-professional, he cannot be mono-characteristic: his psychological functioning cannot be reduced to one or two “character traits”.

These “character traits” are not moreover stable entities which manifest themselves systematically in concert and which could thus describe its functioning whatever the context. They can appear alternately, depending on the situations with which the individual is confronted, his age, his general balance or imbalance, etc. We are entering a minefield here by the possibility of multiple conscious or unconscious confirmation biases, and frankly resistant to the qualitative reductionism of most biographical data and the quantitative reductionism produced by non-Bayesian statistics.

But Suitbert Ertel, who was decidedly a “ally” very cumbersome for the Gauquelins, also made a major mistake by basing himself on the same biographical data as them. His professional status as Professor Emeritus of Psychology should have encouraged him to be more cautious and shrewd. Indeed, he could not ignore that the complexity of human functioning can only largely escape the simple examination of biographies of various qualities, whose psychological notations they contain are often of weak or random relevance.

To statistically confirm or invalidate the relevance of “character traits” associated with the planets, Suitbert Ertel should have relied, in all scientific rigor, on the comparison between these and the results of various standard psychometric tests to which he should have submitted each “champion” professional. This was of course an impossible task for obvious reasons that it is useless to list them all. We will content ourselves with observing that it would have been necessary for all of them to agree to submit to these long and tedious tests, which is a hypothesis so improbable that it does not deserve any statistics, and that most of them were dead, which is a compelling reason.

Nevertheless, nothing prohibits carrying out what the researchers call a “thought experiment”, which Suitbert Ertel did not do and should have done, just like the Gauquelins who, like him, had university degrees in psychology. This type of imaginary experience, which makes up for the fact that the conditions for concrete experimentation are not realizable, is based on the following question: “what if…?” So let’s imagine that all the “champions” professionals from the samples have accepted and been able to submit to these standard psychometric tests.

▶ It must first be considered that most of these tests measure different abilities or inabilities, identified on the basis of criteria that are not standard from one test to another, and that they can produce, applied to the same individual, contradictory or even antagonists, given that human functioning is complex and that applied psychology is very far from being an exact science. It must be taken into account that each type of standard test has a limited field of relevance, that this field may or may not intersect with that of the others, and that it has its supporters and opponents who stir up numerous and often byzantine controversies. Let us nevertheless admit that it is possible to make an improbable synthesis. Or that we can determine, among the large number of these standard tests, the one or those that are probably the most adequate to identify and objectively determine “character traits” identical to those associated with each planet.

▶ The conditions would then be met for each individual to have a standardized psychological profile. Before we start comparing the results of these psychometric tests to “character traits” associated with each planet, it would be necessary to pass to the second stage. Its purpose would be to carry out an evaluation of the multifactorial impact of extra-astrological determinisms which will have contributed to very significantly modifying these “character traits” according to parameters such as heredity, sex, intellectual, moral, socio-cultural level, etc. This essential task having been accomplished, it would still be necessary to determine in which situations and with which frequencies these “character traits” manifest themselves jointly or alternately, etc. And finally, the same should be done for the control sample of about 25,000 “non-champions” Gauquelin data. It is only once all these conditions are met that serious comparative statistics could begin.

▶ At the end of this “thought experiment”, we understand better why Suitbert Ertel neglected to go through the same biographies as the Gauquelins. It’s much simpler and achievable, and after all “the impossible no one is bound”. However, there is an alternative which is within the realm of the possible. It would consist in testing by means of bayesian statistics a rigorous and coherent astrological theory with solid methods of interpretation. With strong assumptions a priori and from a strict experimental protocol well adapted to the object it claims to measure, one would obtain results quite different from those of Gauquelin and Suitbert Ertel. This experiment, although feasible, has never been carried out.

Suitbert Ertel, the main successor of the Gauquelins, died in 2017. It is not known who took or will take over from him, or even if this will happen. And if this is done, it is to be hoped that this or these continuators will be based on completely different hypotheses and on subtle and conditionalist Bayesian statistics. Time will tell… or not.

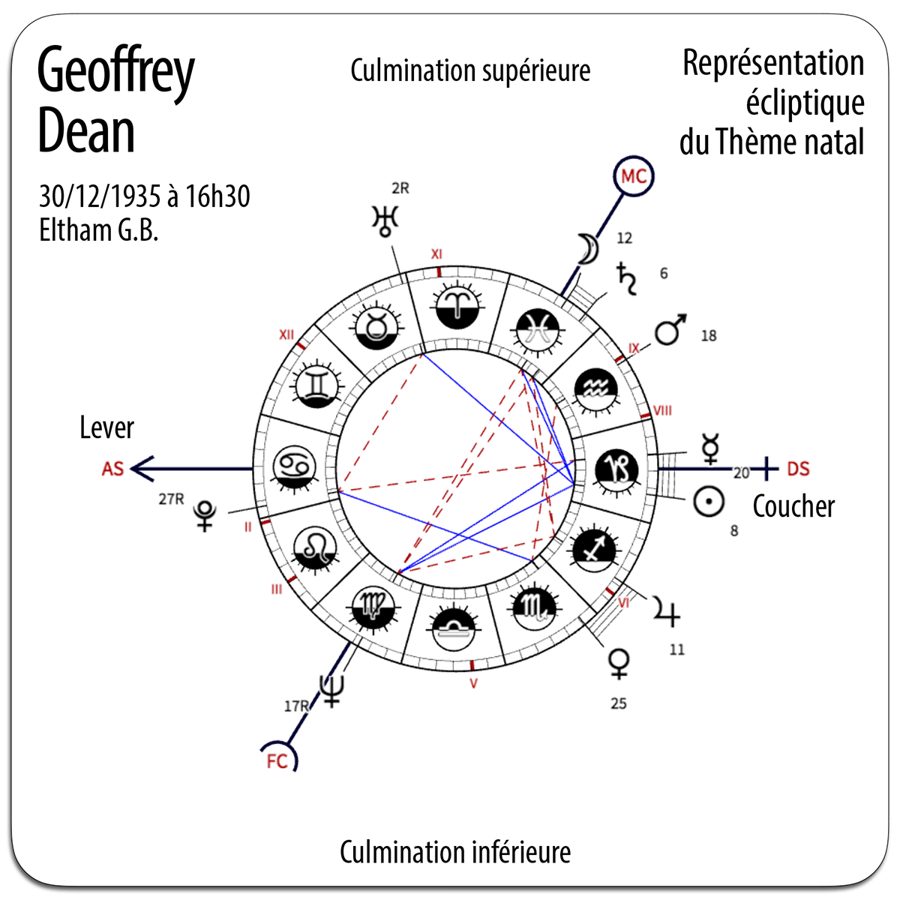

In 2002 a major player in anti-astrologism intervened with a new argument on the stage of the “Mars effect”. It is Geoffrey Dean, an Australian analytical chemist. His case is particularly interesting, given that he was once a hyper-traditional astrologer before becoming a ferocious scorner of astrology. In this capacity he published in 1977 Recent Advances in Natal Astrology: A critical review 1900–1976, a book compiling all kinds of critical research, from the most stupid-simplistic to the most pointed, of which it must be recognized that a large number is relevant and justified. This book has become a veritable bible for the use of anti-astrologers in the English-speaking world. Geoffrey Dean ended up joining CSICOP, where he created the website devoted to astrology, and writes regularly in the Skeptical inquirer, review of this pseudo-skeptical association.

Geoffrey Dean is a special case in the English-speaking anti-astrologer nebula. Ex-astrologer (and president of the Federation of West Australian Astrologers until 1983!) become anti-astrologer, in many respects he is the anti-symmetric, the opposite of Michel Gauquelin, astrologer, then astro-skeptic who became “neo-astrologer”. Both refer obsessively only to an archaic and hyper-deterministic conception of astrology, one to systematically demolish it, the other to statistically extract only a few rare elements which appear as valid. In this deceptive game of mirrors, their apparently opposite positions thus come together on a fundamental point: there is no question for them of testing hypotheses other than those suggested by their conception reactionary of astrology.

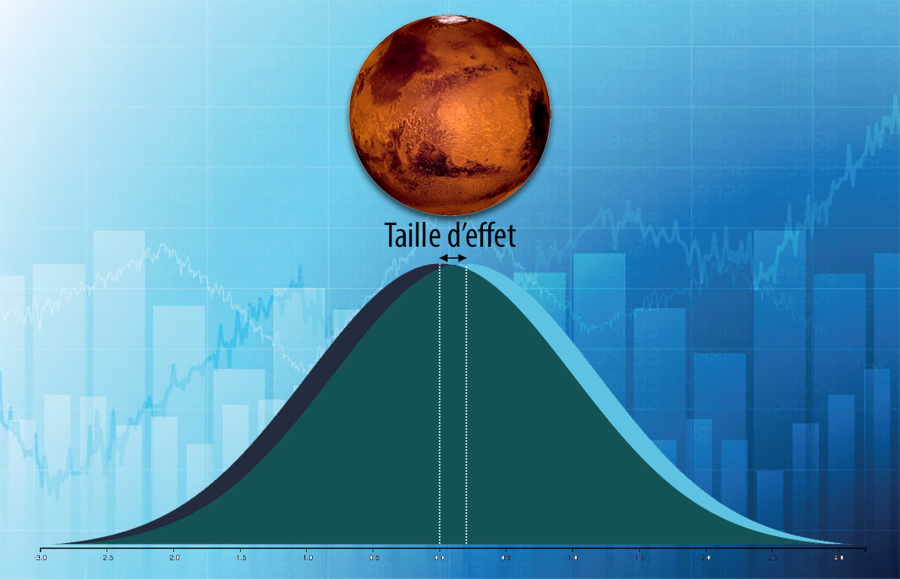

Geoffrey Dean did not participate in the CSICOP frauds concerning the “Mars effect”. He was not elected “CSICOP companion” than in 2003. But he was obviously very interested in Gauquelin statistics, whose possible various astronomical and demographic biases he ruthlessly tracked down. Having failed to find any sufficiently significant to invalidate them, he was the first to have the idea of applying to them the notion of “effect size”, which is very different from that of deviation from the mean. We have seen that the deviations from the mean of these statistics were of the order of 10 to 25%, which is not huge but is considered significant. Word “significant” in statistics does not mean who “has a meaning”, but “which is no coincidence”, i.e. which presents a deviation from normal which is too high to be explained by the natural variability of the composition of the group tested. These deviations from the mean were different for each profession concerned and depended on the size of each sample, the vagaries of these samplings being able to clearly affect the value of the estimates. A deviation from the mean is considered significant if the measurement of statistical significance is below the significance threshold that has been set, generally 5% or 1%.

But on a large sample (eg more than 1000 people), the deviations from the mean can be estimated with more precision, which makes it possible to better distinguish which of the correlations are really significant. This is where the concept of “effect size”, which is a measure of the power of the effect observed from one variable to another, here on large samples of populations of professional celebrities, all the professions (the variables) then being considered as belonging to a single sample. Effect size is measured using various standardized scales. The one that Dean chose ranges from a scale of 0 (zero effect) to 1 (perfect correlation). The larger the effect size, the greater the deviation from the null hypothesis (= not “march effect”) is large and vice versa, the null hypothesis corresponding to an effect size equal to zero. The size of the effect thus makes it possible here to quantify the amplitude of a deviation from the mean, without prejudging its statistical significance, the importance of a significant correlation within a large sampling (professions in general) bringing together several sub-samples of smaller numbers (each profession in particular).

Geoffrey Dean calculated that on this scale of 0 to 1, the effect size of all of Gauquelin’s statistics for occupations was about 0.045. This did not question the statistical significance of these results but confirmed that the correlation was very weak, a weakness which was not to displease Dean, even if he would obviously have preferred an effect size equal to zero… which he will try to obtain by another means, using the quasi-psychedelic argument of the “social artifacts” which we will dissect further.

Concrete example of what effect size implies: imagine that the HRD (Director of Human Resources) of a company relies exclusively on Gauquelin statistics to decide whether to hire a non-famous professional candidate (this which is generally the case) for a position with a profile “marsian”. This HRD would then only have a 50.0001% probability (1 chance in 1 million) of finding the right person, which is very close to the laws of chance. And if this candidate belonged to the 0.006% of the population considered famous, this probability would be 52%. It’s a little better, but still clearly insufficient to decide on hiring on a rational criterion, that is to say with maximum certainty of having found the profile “marsian” Ideal for the position to be filled. It therefore goes without saying that the results of the Gauquelin statistics would be of no practical use for the decision that this HRD must take.

It also implies that Gauquelin statistics are of almost no use to an astrologer having to decipher a natal horoscope. He can only retain two positive results for his practice. The first is an experimental confirmation of the importance traditionally given to sunrises, sunsets and culminations as essential factors of planetary valuations. The second is a reassessment of the extent and location of the zones within which the Planets therein can be considered dominant. That is all, it is very little and it is nevertheless decisive.

By arguing the tenuousness of effect size to minimize the observed significance of Gauquelin statistics, Dean’s goal is first and foremost, and with much bad faith, to create a… impressive effect size in the minds of those who read it. In other words, he tries to throw anti-astrologer powder in his eyes. A weak effect is simply an effect that is difficult to observe. This is the case with many physical effects that are no less real. This difficulty of observation therefore requires above all to carry out new studies, for example on larger samples of natal charts. It may also require refining the initial hypothesis or modifying certain parameters in order to verify whether these initial changes have an impact on the statistical significance and therefore on the size of the effects. However, these new studies would come up against two difficulties inherent in their purpose, namely:

▶ The celebrity criterion correlative to very great professional successes in relation to the planetary positions in the local sphere on which the Gauquelin astro-statistics are based can by definition only concern very small samples of the population. Not everyone can be a “champion” in his domain. New sampling should therefore be carried out from populations born after 1950, in order to renew the stock of “champions” in the same professions. It would then be possible to apply the effect size measure to the data accumulated between 1800 and for example 2010, and to observe whether this size increases or decreases; however, we would come up against another difficulty: except in sport, the average age from which we can observe an undoubted celebrity in relation to professional success can be at least 30 years old.

▶ Which means that a study hypothetically conducted in 2020 could only look at the class of individuals born between 1950 and around 1990. In such a short period, the likely number of “champions” famous professionals will necessarily be hyper-reduced in comparison with those of 1800–1950 (it can be estimated at around 425). This small sample would affect the significance, measured in effect size, of the new statistics that would thus be produced. Further adding these new “champions” would only marginally change the cumulative effect size of all of these stats. A new study would therefore have to be carried out in 2100 to obtain a figure comparable to that obtained for 1800–1950. And it is likely that the new 1800–2100 sampling thus obtained, which would cover only about 3200 Birth Charts, would not vary the size of the effect very significantly, given the relative smallness of its numbers.

▶ Researchers undertaking this task would nevertheless face two major difficulties. The first lies in the accuracy of birth times: average-low before 1950 in countries with efficient Civil Registry and free access (which is no longer the case, for example, in many of the USA), it became very strong after this date. This parameter should be taken into account. The second difficulty stems from the fact that the exponential development of the media sphere since 1950 has very likely had a significant effect on the measurement of celebrity. This other parameter, which is difficult to quantify objectively, should also be taken into consideration.

▶ As for refining the initial hypothesis, it would of course require completely redoing the statistics for 1800–1950 and doing those for 1950–2010 or 1950–2100 on this modified basis. But we do not really see what kind of refinement this could be, except to move the celebrity cursor in relation to professional success and/or to take into account the new professions that have appeared since 1950 by applying the same refinement to them, and this always with necessarily reduced samples.

▶ We thus come back to the fundamental problem posed by the starting hypothesis, which is that of the supposed correlation between the “champions” professionals whose success in their field has made them famous, and planetary positions in the local sphere. It is this that has been validated as statistically significant although with a small effect size, and not an astrological fact in itself. It is indeed the simplistic and implicitly hyper-deterministic — and in this sense, astro-fatalistic — character of this supposed correlation which led to the statistical observation of a weak signal, and which is consequently the first cause of the weakness of this signal. It could not be otherwise. If Geoffrey Dean had been a serious critical researcher rather than a disappointed and vengeful fatalistic ex-astrologer, he would have raised this objection and developed this argument rather than focusing on effect size and, as we will see later, on social pseudo-artefacts.

▶ The problem of the small effect size of the observed signal thus has a character paradoxical. Indeed, for this weak signal to have been able to emerge significantly from the background noise of the multitude of other signals, and therefore to appear despite the interference that affected it due to the hyper-deterministic nature of the initial hypothesis, the initial signal had to be singularly strong but of a hypo-deterministic nature, which is consistent with a conditionalist conception of astrological effects. Because no offense to Dean, Gauquelin and most traditional astrologers, astrological effects are of a weakly deterministic nature. This quote from Johannes Kepler, astronomer-astrologer, illustrates this well in a striking agricultural comparison: “How does the lay of the sky at the time of birth determine character? It acts on man during his life like the strings that a peasant ties at random around the gourds of his field: the knots do not make the gourd grow, but they determine its shape. Likewise the sky: it does not give man his habits, his history, his happiness, his children, his wealth, his wife… but it shapes his condition.”

▶ Let us keep this Keplerian image to illustrate the paradoxical character of the problem of the weakness of the signal measured by the size of the effect. In this astro-cucurbitacean perspective, the founding hypothesis of Gauquelin statistics — that is to say what they claim to measure — is not the string with its weight, its diameter, its length, the fibers of which it is made, the resistance of its nodes, etc. What they claim to actually measure is a de facto amalgam of the squash and the string that gave it a certain shape. And this without worrying about the quality of the variety and the quality of the initial seeds, the land on which these plants grew and the gardener who cultivated them, or even the aggressions to which they may have been subjected by of the pumpkin bugs, which also attack squash and seriously harm their development.

▶ This gross confusion between knotting celestial strings and knotted earthly gourds is not a creative bisociation. The strings and the knots they make should in principle not weigh much if we compare this weight to that of the gourds they enclose. And this is where the paradox lies: the very low weight of the strings should have been statistically drowned in that of the gourds to the point that the hypothetical action of the strings on their shapes cannot be identified as such. But that is not what happened. Despite the very strong signal constituted by the weight of the large gourds, the very weak signal of the weight, and therefore of the apparently marginal action of the thin strings on the gourds, was nevertheless detected. From this fact we can only draw one conclusion: this very weak signal can only have produced a very strong effect. The enormous weight of professional gourds and their “champions” famous could not completely shield that of the planetary strings which determine them tenuously but effectively. The weak signal paradoxically masks a strong signal, the size of the effect of which has not been directly measured by Gauquelin statistics and who is indifferent to big strings of the courgesque arguments from Dean.

▶ It is these planetary strings of which future statistics genuinely concerned with apprehending astrological reality will have to measure the effects and the size of these. These experiments will therefore in the future have the obligation to refrain from confusing these strings with the objects, human or otherwise, whose form they partially determine. And this by contextualizing these planetary effects within other terrestrial, extra-astrological determinisms, which modify their magnitude, intensity and qualities. Suffice to say that this kind of study is totally beyond the reach of classical statistics, but not of Bayesian statistics, which could get closer to astrological reality without being able to grasp it in all its irreducible complexity.

The application of the effect size measure thus brought Geoffrey Dean little consolation, that of putting the Gauquelin statistics into perspective by making apparently the even weaker astrological signal… but still just as statistically factual. And we have seen how the power of weak rhythmic, cyclical and repetitive signals like those of the stars of the solar system should not be underestimated.

The invocation of the size effect with the statistician gods having not been enough for Geoffrey Dean to defeat the astrological dragon, he had a new idea: that of concentrating on what he called the “social artifacts”, the “social artifacts”. These can be defined as the tendency that some parents may have to give their children a false date and/or time of birth based on beliefs, superstitions, cultural or religious conditioning, habits, interests or social amenities. Dean has lumped together this disparate set of predispositions to Civil Registry fraud under the umbrella term “attributions”. This notion explicitly implies that the hypothetical Gauquelinian astrological influences could in fact be “attributed” to those social artifacts that the various cheating committees would have overlooked.

▶ Beliefs affecting the validity of the declared time or date include, for example, the Friday 13, the witches sabbath days (superstitions), Christmas Day or other dates of the Christian liturgical calendar (religious faith). In the first case, there is indeed a slight deficit of births on Friday the 13th (there were approximately 190 between 1800 and 1950), during the Sabbath days, which vary widely according to the place, the days considered as “unlucky” and the days of new moon, and slight excesses of births on the days of Christian festivals, the days considered “lucky”, the days of the full moon and the days of the equinoxes & solstices.

▶ In the second case, it was observed by Suitbert Ertel that out of a population of 2390 priests and monks born in the same period, 39% showed an excess of births on Christian feast days. This deviation from the theoretical average is indeed a social artefact with a real impact on the Gauquelin data… but it does not at all explain the reason for the abnormal frequencies of priests born during the peak hours of Saturn noted by the statistics.

▶ Pure astrological belief can also intervene, a certain number of parents being tempted to officially have their child born before or after the true date, which Geoffrey Dean does not mention while Zodiacal Signs are easier to know than planetary positions. A good indicator of these kinds of social artefacts will therefore be the number of births declared before or after midnight. And Dean actually found that there was a birth deficit at those times.

▶ Apart from social artifacts based on beliefs, we can cite those that originate in economic interests (dates of changes to tax regimes, for example). They very probably exist, but it is practically impossible to assess their effects on Gauquelin statistics, for lack of reliable data. We can therefore only conjecture about them in a vacuum, which Dean did not hesitate to do.

The problems posed by the inaccuracy or falsity of natal times can have multiple involuntary causes (in the vast majority of cases) or voluntary (the small minority on which Geoffrey Dean focused). Before examining them, it is necessary to briefly present the three systems for dividing up the local sphere used by Michel Gauquelin to establish his statistics. Indeed, real or falsified natal times and division into sectors are two closely related phenomena.

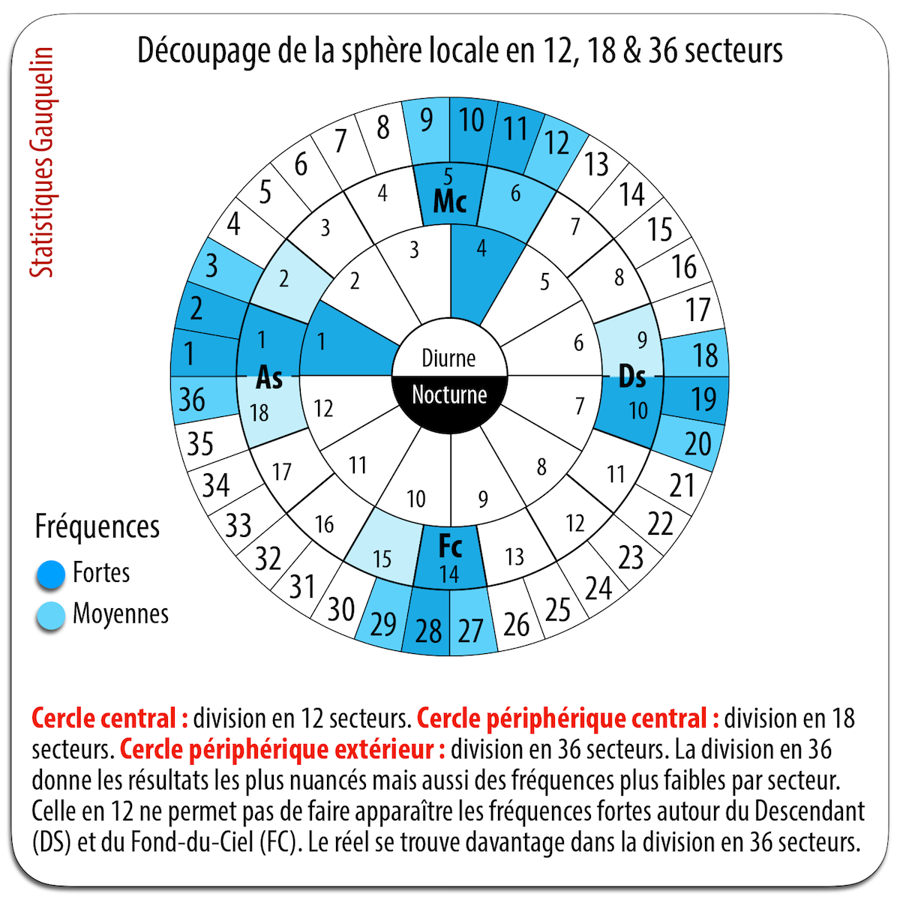

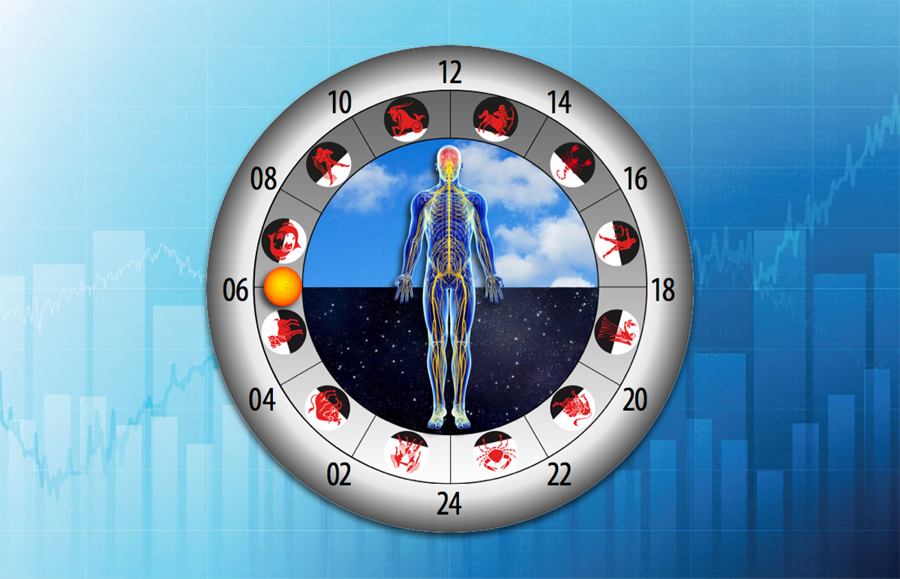

The local sphere is structured by the horizontal (Ascendant/Descendant axis) and meridian (Middle-of-the-Heaven/Back-of-the-Sky axis) planes. From the beginning of his research, Michel Gauquelin decided to divide it into 12, 18 and 36 sectors, of equal extents and durations, in order to calculate what was the distribution frequency of the planets in each of them in 24 hours.

These different breakdowns obey a common statistical law. It can be stated as follows: the smaller the number of sectors, the greater the probability of observing frequencies much higher or much lower than the expected theoretical average. Conversely, a greater number of sectors will lower these frequencies by diluting them, which can make them statistically less significant, but can also reveal significant frequencies which could not be observed in a division into a reduced number of sectors. It follows that a division into 48 sectors, for example, would require extremely high deviations from the expected average for any planetary effect to be statistically observed.

It also follows that for identical astronomical phenomena, different divisions induce different distributions by sectors, and will or will not show different positive or negative frequencies, which range from the most schematic (12 sectors) to the most nuanced (36 sectors). If effects are observed, i.e. significant deviations from the expected average, they will thus be stronger and therefore more spectacular in the division into 12 sectors, weaker and therefore less impressive in the division into 36 sectors. The real is not situated in these arbitrary zooms in or out imposed by the statistical tool. It can only be observed in the reasoned comparison of the effects of these various sectorisations. And the most spectacular are not the most real.

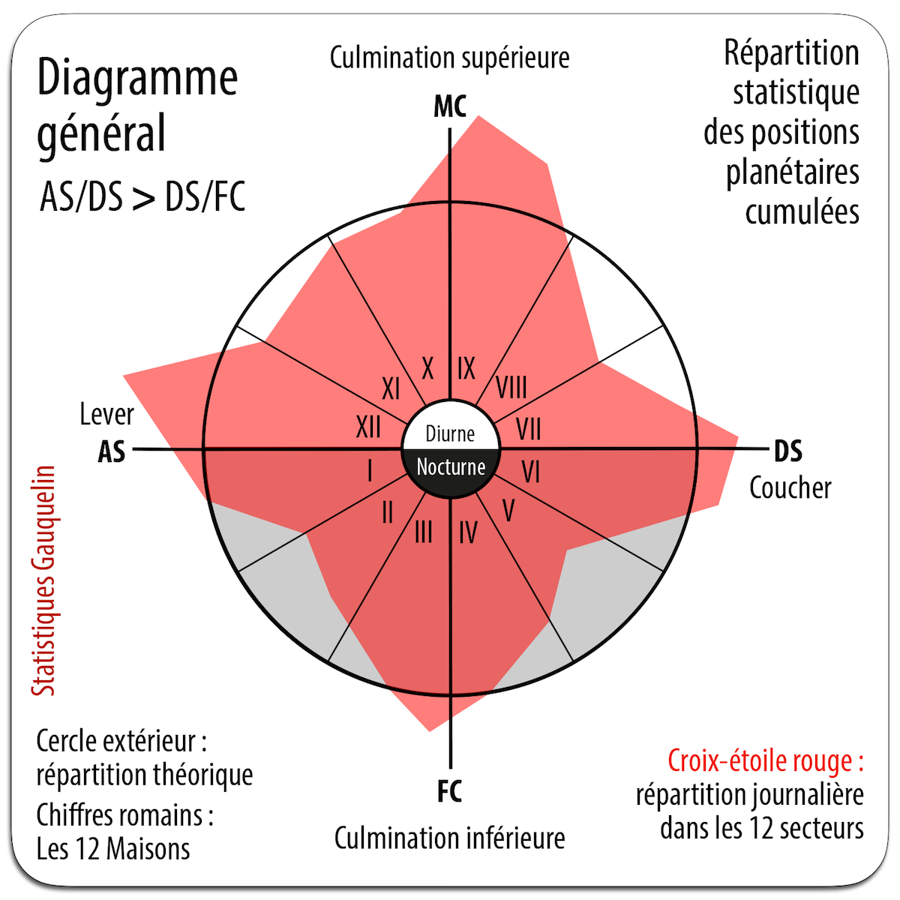

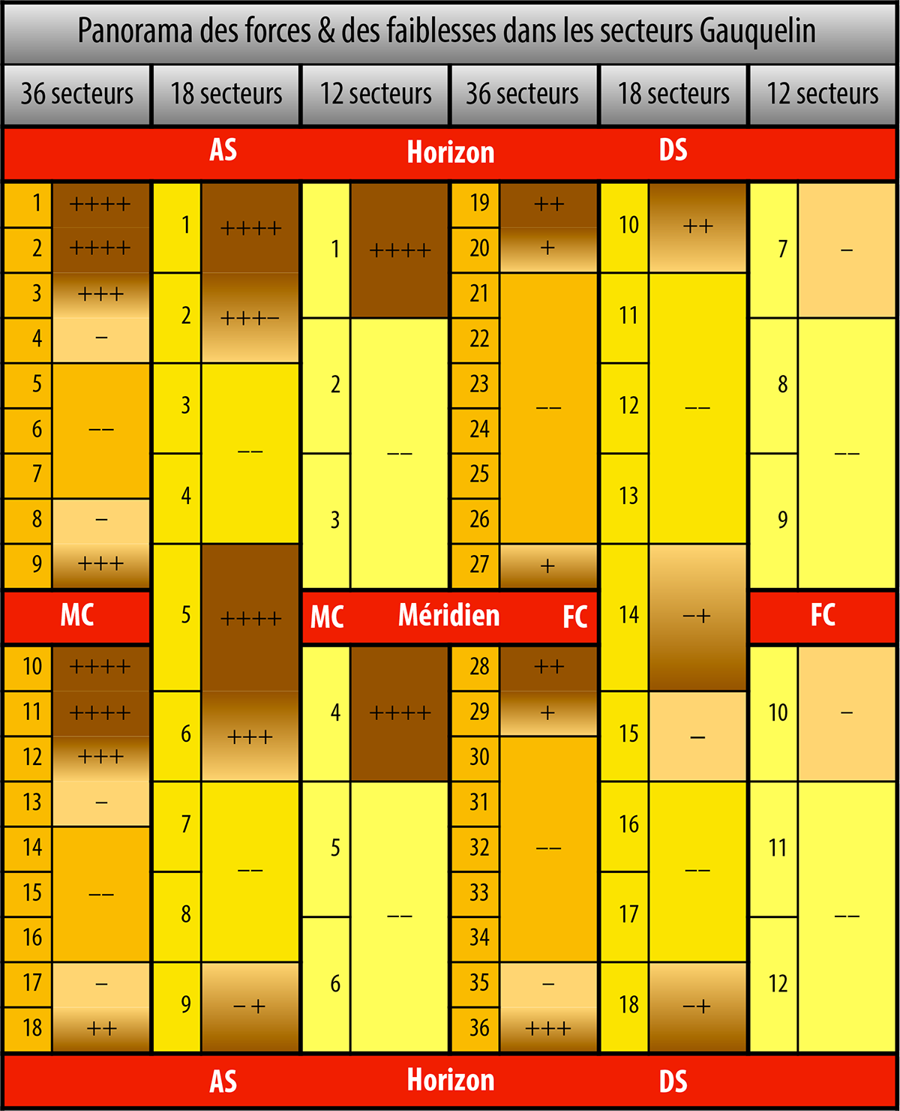

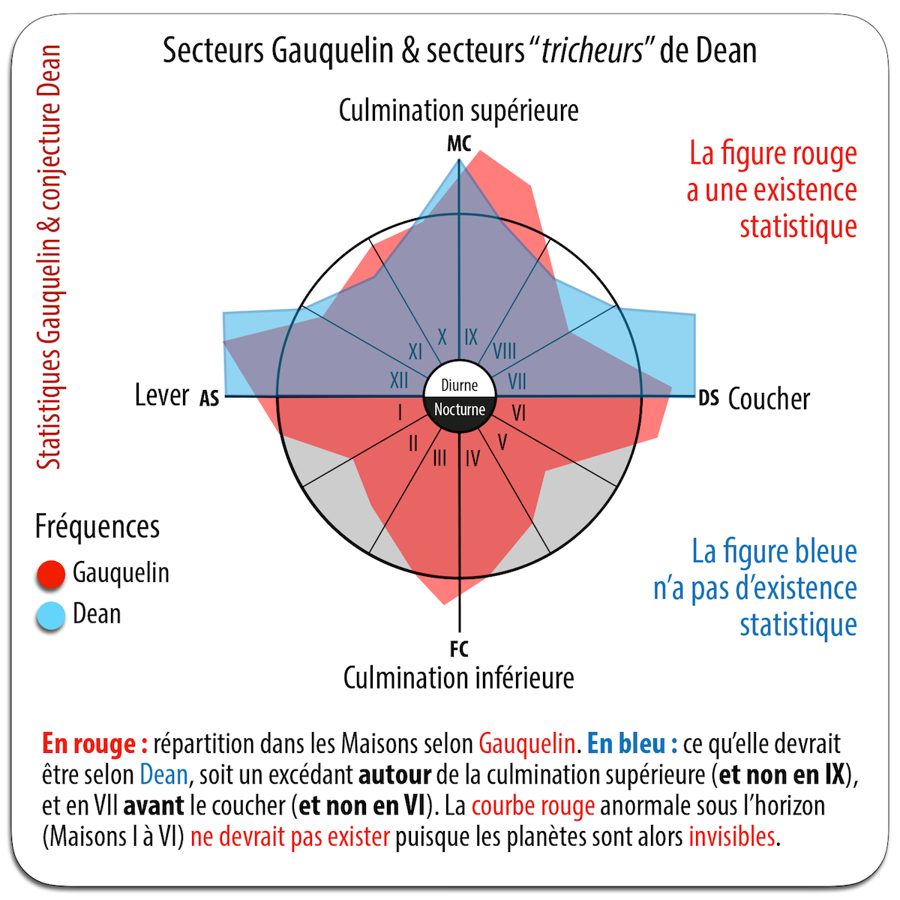

▶ The first diagram below shows the effects of frequencies obtained for the division into 12 Houses numbered in Roman numerals in the senestrogyrate direction (anti-clockwise). It was produced by Michel Gauquelin by compiling the results obtained for each planet. The circle represents the theoretical distribution mean. The red figure in the shape of a cross or a star is characteristic because it is regularly observed, with variations induced by the size of the samples concerned. It represents the observed distribution frequencies. The parts that overflow the circle represent the statistically significant excess frequencies. Independently of the quantitative criterion of high, low or zero significance, this shape illustrates the existence of a qualitative criterion: it shows that a characteristic effect occurs near the horizon and the meridian. We observe that this effect is about twice as important at the Ascendant (AS) and at the Midheaven (MC) than at the Descendant (DS) and at the Imum Coeli (IC). Which can be translated as: AS/MC > DS/IC. The formula also indicates that planetary effects are more noticeable above (daytime hemisphere) than below the horizon (nighttime hemisphere).

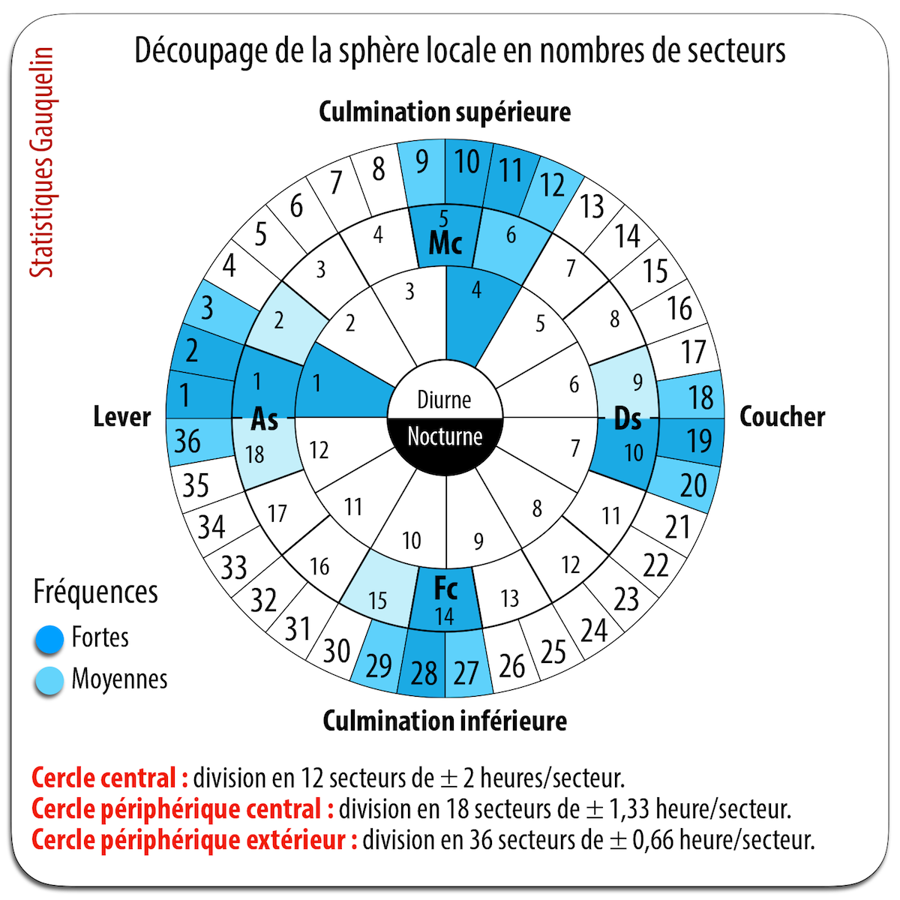

▶ In the panoramic diagram below, the reference to the 12 astrological Houses numbered in the senestrogyrate sense has been dropped. It has been replaced by the division into 12, 18 & 36 sectors numbered this time in the dextrogyrate direction (clockwise), which is that of the daily movement of the planets around the horizon. Shades of blue indicate the relative valuation power of the sectors. The “key sectors” are in dark blue. The central division into 12 sectors only shows the frequencies of the planets in its sectors 1 & 4 as significant. outer peripheral division into 36 sectors, more nuanced, reveals significant frequencies which could not be identified by the division into 12 or 18 sectors.

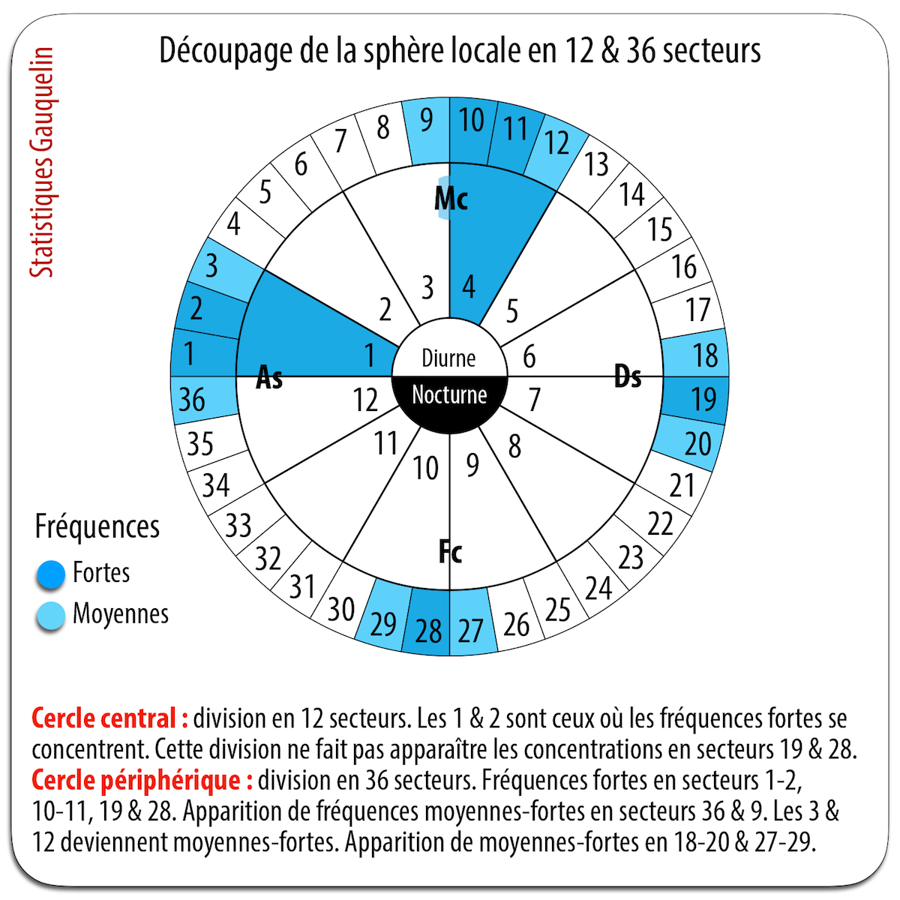

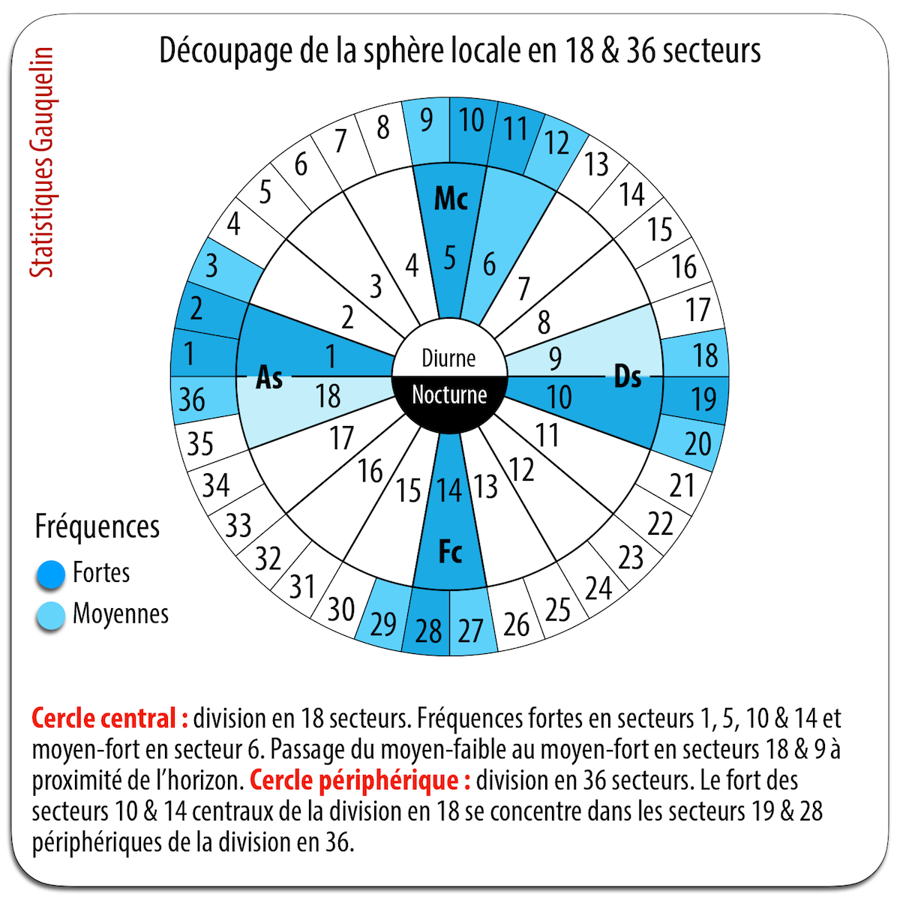

▶ The following diagrams illustrate the results compared, and the analysis that can be made of them, depending on whether the local sphere is divided into 12, 18 or 36 sectors. In any case, you must never forget to associate the quantitative criterion (frequencies by sectors) with the qualitative criterion (general model in the shape of a star-cross superimposed on the horizontal and vertical axes). So for example, even when the planets have lower than average frequencies near their setting (DS) or their lower culmination (IC), this cross-star shape remains. It indicates that something specific is happening in these areas, and that this qualitative effect cannot be reduced to its quantitative dimension.

We will see later that Geoffrey Dean relied exclusively on the division into 12 sectors to conjecture on the social artefacts which, according to him, would be a determining cause of the Gauquelin statistics. It is a deliberate choice and ad hoc which allows him to ignore the sectors of sunset and lower culmination, whose frequencies in sectors invalidate his hypotheses.

▶ The overview table below summarizes the comparative relative strengths & weaknesses of the planets according to whether their position frequencies are divided into 12, 18 & 36 sectors. These strengths and weaknesses are coded as “+” (strengths) and “–” (weaknesses). Brown colored areas represent areas of strength. We observe that the division into 12, very summary, gives the impression that the dynamics of strengths and weaknesses seem produced by a non-linear function producing brutal alternations. This impression is contradicted by the division in 36, which suggests that this dynamic is the product of a linear function: the transition from strong to weak (and vice versa) does not occur suddenly, but gradually, progressively. It is possible that the general curve is produced by the paradoxical combination of a linear function and a non-linear one, the second introducing threshold effects inside the first. But this is only conjecture, a hypothesis whose relevance remains to be verified.

The actual situation of “key sectors” defined by Gauquelin statistics directly depends on the accuracy of birth times. The preceding diagrams and table are directly indexed on this fundamental data. However, for the period (1800–1950) on which these studies are based, accuracy is the exception rather than the rule. Evidenced by the very high frequency of the hours “round”, which is around 80% when it should be 17%, which means that most of these hours “round” are actually rounded hours. From 1930 to 1960, this proportion rose to around 35%, and it was not until 1960 that it reached its normal threshold of 17%.

In the less imprecise cases, i.e. approximately after 1900, we know that this hourly rounding was generally carried out in hourly units (e.g. 08:00 instead of 07:45) or half-hourly (eg 07:30 instead of 07:15) higher. In the most imprecise cases, therefore approximately before 1900, we do not know the margin of this imprecision. But we can estimate that it was most likely and most of the time much larger. It can then be assumed as a very probable and reasonable hypothesis that in these cases the declared time was generally later than rather than earlier than the exact time, which goes in the same direction as rounding up to the next hourly unit. It follows that we gain by thinking that the real beginning of “key sectors” is about 10° before the beginning given by the Gauquelin statistics 1800–1950. This is the result produced by the same statistics after this period, and this is confirmed by the non-statistifiable experience data which also have their value, qualitative more than quantitative.

The resolution of the complex problem posed by these timing uncertainties and inaccuracies is therefore very uncertain, and thus lends itself to all sorts of hypotheses and conjectures, a very large number of which are based on assumptions made from mostly unverifiable data. It is imperative to have this general panorama in mind to judge the relevance and rationality of some of Geoffrey Dean’s arguments, and especially the impertinence and irrationality of most of them.

The imprecision of reported birth times constitutes another form of social artefact, very long associated with the source of technical artefacts that constituted the precision of clocks. This problem is further developed in the section devoted to “Birth time accuracy issue”. We will limit ourselves to pointing out that in the 19th century the imprecision of the hours declared was quite great and varied depending on whether the births took place in the towns or in the villages. But even at the beginning of the 20th century, precision was far from being the rule, as evidenced by a major study undertaken by Françoise Gauquelin in 1959.

It thus compared, without giving the size of its sample, the hours recorded between 1928 and 1950 in Parisian hospitals and the Civil Registry. She found that about two-thirds of births between 1928 and 1934 showed an average difference of 19 minutes, most of which was due to rounding of the hour. Hospital time was recorded to the nearest 5 minutes, while town halls rounded 80% of births to the hour or half hour. 5% of the differences were less than 15 minutes, and 15%, so 1 in 7, were between 1 and 3 hours. Françoise Gauquelin also noticed that from 1935 there was only a difference of about 10 minutes.

Since most of the Gauquelin data concerning professionals predates 1928 and is much more rural, and therefore includes a much larger number of extra-hospital births, it is reasonable to conjecture that the imprecision of birth times was significantly higher. This is all the more so since rural births were not always declared on the same day, those who declared them had not always been witnesses to the birth and the accuracy of the time depended on that of the clocks. That’s a lot of variables and unknowns.

Geoffrey Dean was of course engulfed in this watchmaking breach. The 15% of births in Paris in 1928–1934 focused his attention. The difference of 1 to almost 3 hours between the time of hospital declaration and that of Civil Registry declaration cannot in fact fall into the category of rounded hours due to an irrational but very administrative concern for standardization. This is clearly another phenomenon. Before pouring into conspiratorial conjectures based on cheating parents, we can seek the causes in very probable errors or negligence in transcription and probably also in the fact that in a certain number of cases the time could be declared at the Civil Registry with a “stating who had not even witnessed” (Françoise Gauquelin, another study in 1993) from birth. In both cases, these very large inaccuracies or time inaccuracies can come into play either before or after the time declared to the hospital. The same is not true for the 80% of births whose times are rounded to the hour or half hour: we know from experience that this rounding is done almost systematically in favor of the higher unit (15:00 instead of 14:50).

If Geoffrey Dean focused on the 15% of births in Paris from 1928–1934 with a difference of 1 to almost 3 hours between the time of hospital declaration and that of Civil Registry declaration, it is for two very specific reasons. The first is that a “key sector” of Gauquelin defined by the division of the local sphere into 12 equal parts corresponds to a duration of 2 hours, which is the average time of presence of a planet in this sector. A difference of 1 to 3 hours is therefore sufficient for this planet to be able to pass from one sector “strong” to another “weak”, which would inevitably affect the general profile of the statistics since it would concern 1 out of 7 cases.

However Dean calculated that it was enough for 1 case voluntarily or involuntarily fraudulent out of 30 so that, taking into account their size of effect, the Gauquelin statistics can be reduced to a pure social artifact caused both by the inaccuracy of the hours of birth, their roundings and in 15% of cases their falsity. But from 1/7 to 1/30 there is still room. 23 remain to be found before being able to ruin any relationship between men and the stars. These 23, Dean thinks he unearthed them by conjecturing that this general lack of precision would create a context favorable to the cheating of a hypothetical and indeterminate number of parents wishing to have their children born at the hours of power of certain planets rather than others. We will demonstrate later that this hypothesis is not only specious, but also irrational and contradicted by the facts: this is a conjecture that has its source in a characterized anti-astrologer cognitive bias.

But before that we must carefully examine the pure unverifiable conjecture of Geoffrey Dean. By a biased sleight of hand, he claims that an average difference of about 2 hours between the real time and the declared time could cause a planet to pass from a strong sector to a weak sector of the local sphere divided in 12. However, this is only true when this planet is exactly at the end of a strong sector in the daily movement (thus between sectors 1–2 & 4–5), and for sectors 7–8 & 10–11 this average gap is about 40 minutes). But if this planet is at the beginning of a strong sector (so between sectors 12–1 & 3–4), it will stay there for about the same 2 hours (about 40 minutes for sectors 6–7 & 9–10)… and the distribution frequencies will then remain the same, which Dean fails to specify. It is the same for a planet located exactly in the center of a strong sector 1–2 & 4–5: even with a difference of a little less than 1 hour, it will always be in this same sector, but at its end.

Contrary to what he claims, a discrepancy of 2 hours or even 1 hour is not enough to ruin the Gauquelin statistics by reducing them to a measure of social artifacts. The same is true if we divide the local sphere into 18 sectors of 20° (1 hour 20 minutes) or 36 sectors of 10° (40 minutes) in the 15% of cases which interest it the most, and whatever the cause of the inaccuracies or falsehoods, whether unintentional (declaration and/or transcription error) or voluntary (very hypothetical and doubtful high proportion of cheating parents due to in-depth astrological knowledge). Moreover, he could and even should have, to be as rationalist as he claims to be, applied the same arguments to the 80% of births rounded to the hour or half hour, given that statistically, we should not observe that 17% of round hours, which corresponds to their real frequency. But if he had pursued this specious reasoning to the end, he would have been forced to conclude that Gauquelin’s statistics related only to massive errors and that they only measured these while still leading to d Strange planetary distributions in the local sphere constituting an unmistakable statistical fact, which is an assumption that can be described as irrational and charlatanesque.

It is also interesting to note that Michel Gauquelin, in 1979, was sorry to note, while carrying out new statistical studies, that the “Mars effect” seemed to decrease for births after 1950, when the frequency of round hours fell from 35% to 17%. He attributed this phenomenon to births “unnatural”, i.e. medically induced. However, the cause was different: it resided above all in the greater precision of birth times, which led to a change in “key sectors”, which now moved astride the horizon and the meridian. Suitbert Ertel carried out a statistical check of this new phenomenon, relating to the comparison between a sample of 117 sports champions born after 1946 with another of 319 born before. Although the sizes of these samples were small, the results were, according to him, significant and led him to find that the “Mars effect” did not disappear, but remained identifiable only in the division into 36 sectors. Meaning it concentrated more at the beginning of Houses I, X, VII & IV, and much less at the end of Houses XII, IX, VI & III, a logical effect of less and less rounded hours at the superior unity… and much less removed from the assertions of the astrological tradition than Gauquelin wished!

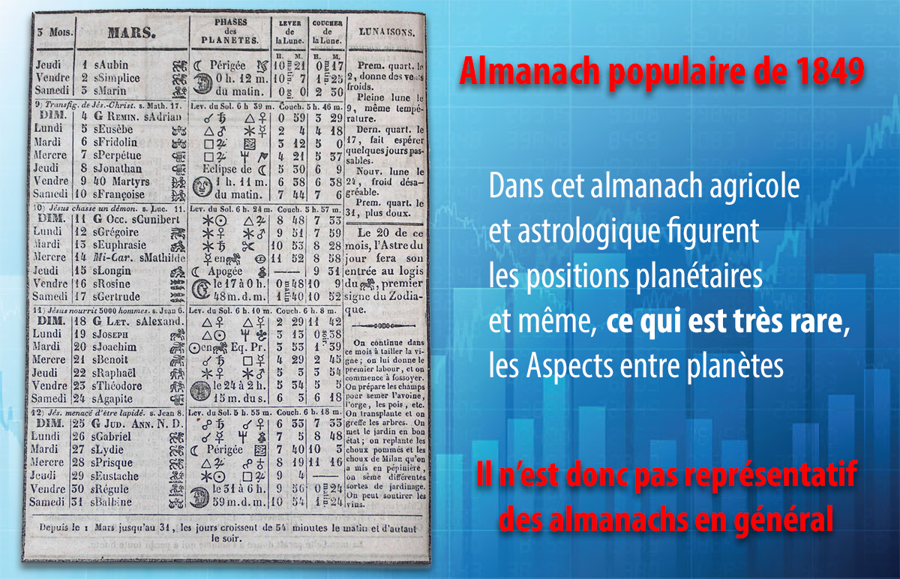

Either way, these perinatal clockwork issues did not explain why different planets were statistically linked to different professions. Geoffrey Dean then looked into the case of almanacs, which were still very popular in rural Europe and the United States during the birth period of many of the individuals covered by the Gauquelin data. Since some of these almanacs give the approximate times of the risings, sets and upper culminations of the Moon, the Sun and (sometimes) the planets, he wondered if many parents would not have decided to declare birth times coinciding more or less with the beneficial or malefic character attributed to these stars in order to prevent their offspring from being born under a “bad star”.

This attribution hypothesis, which Dean called the “perinatal control” parental, is simply unverifiable, anachronistic and grotesque. But before demonstrating this, it is necessary to consider the phenomenon of almanacs, their real content and the services expected from them by the mostly rural and uneducated populations who read them or had them read to them by neighbors.

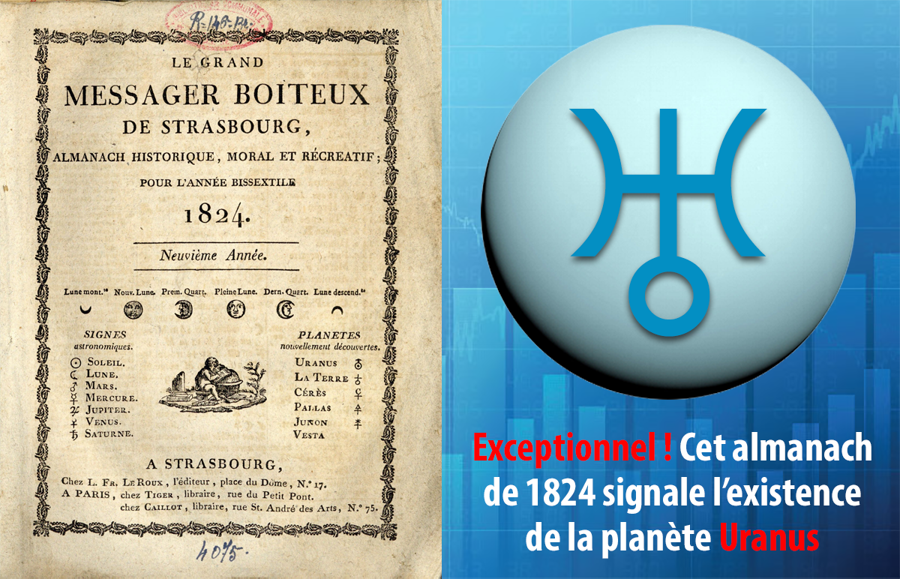

Of poor quality from every point of view, they were volumes of 100 to 150 pages. They were indeed very popular since they were printed in around 4 to 6 million copies from all publishing houses, to take only the example of France. Their sales were directly related to their content “astrological”. Almanacs without reference to the stars did not exceed 2,000 to 10,000 copies sold, those with a cover displaying any astral and/or prophetic content reached sales of 50,000 to 200,000 copies. Astrology or what took its place was therefore an essential selling point… until the 1850s. Indeed, from this decade onwards there was a rather broad general movement of gradual reflux of astrological or pseudo-astrological references and predictions. astrological, often replaced by “proverbs and moral or common sense recommendations”, while the meteorological and astro-meteorological forecasts were maintained, which had a clearly utilitarian purpose even if irrational and illusory. If the 19th century was indeed a golden age of the prophetic almanac if not really astrological, so it was essentially only during its first half.

The following quotations are taken from the study unless otherwise stated Astrological prophecies and predictions in the popular almanacs of the 19th century produced by Arnaud Baubérot, lecturer in contemporary history at the University of Paris-Est Créteil (UPEC) and researcher at the Center for Research in Comparative European History (CRHEC). Here is how he presents these editorial productions: “These almanacs are addressed to the working classes of the countryside, that is to say to a social group that never resorts to writing to talk about itself, and a fortiori to its reading practices. Moreover, its consumption of mass-published volumes, of poor formal quality, without literary value and which seem to recycle archaic content, is always decried by the cultural elites, when they deign to mention it.”

This distinction between cultural elites and rural working classes is essential for our purpose, and we will come back to it. Let us content ourselves for the moment with noting that the upper classes were not readers of these almanacs which were not intended for them. However, as Michel Gauquelin remarked in his Dossier of cosmic influences about the “champions” astro-professionals, “in broad terms, two-thirds of celebrities were drawn from the top 5% of the population, made up above all of the wealthiest and most intellectual people. A professional propensity is transmitted from generation to generation.” If we consider the fact that sports champions are recruited mainly from the lower classes and intellectual or artistic champions from the upper ones, and that the sample of the former only represents about 1/6 of the total number of professions, we can surmise that around 90% of “champions” Gauquelin belonged to a rich and educated population who read little or no almanacs. Accuracy is important, all the more so since the end of the 17th century, astrology was considered by these elites as a vulgar superstition. They preferred to indulge in new pseudo-scientific beliefs.

These almanacs obviously did not deal only with astrology or prophecies and the number of pages devoted to them varied according to the titles by approximately 1/10 to 1/5. They indicated until about half of the 19th century “the table of days and lunations, the indication of the movable feasts of the liturgical calendar, sometimes the list of reigning families and members of the government, but above all weather forecasts, prophecies for the coming year and for each of its months, the indication of favorable days to undertake certain works, to begin a journey, to bleed or take medication… all mixed with instructive or entertaining chapters. The signature on the cover no longer designates an authentic author but the name of an astrological celebrity, real or imaginary, cited with the aim of baiting the customer. Predictions are most often limited to stereotyped formulas that printing employees will draw from the depths of prophetic literature from previous eras or plagiarize from other editions.” This caricatural form of astrology was therefore essentially a loss leader, a selling point which nevertheless met a real expectation of readers in search of fabulous or marvelous stories. Something to distract oneself from hard rural work during the long winter evenings and not to learn about the astronomical phenomena that underlie astrological discourse. The astronomical part was most often reduced to the indication of the lunar phases, the dates of eclipses and the observation of the night sky.

This popular astral belief had only a very distant relationship with scholarly astrology. She was only one of the manifestations among others of a “paganism” rural whose major components were magic, witchcraft, belief in ghosts, spellcasters and the practice of various forms of divination. Moreover, it is essentially these extra-astrological phenomena that are recounted by the literature devoted to popular rural beliefs of that time. It thus appears very unlikely that these rural people gave great importance to their Sun Sign at birth or to those of their neighbours. However, the Sun sign is the simplest and most accessible astro-identity marker for everyone. How can we then imagine that these populations could have cared about knowing the dominant planets at the birth of their offspring?

Arnaud Baubérot puts forward three hypotheses to explain the presence of astrology in almanacs, and they are entirely well-founded and rational. He thus considers that this presence falls under three distinct registers: that of the natural association between the seasonal cycles and the succession of the zodiacal signs, that of astro-meteorology and finally that of the pure literature of imagination and distraction.

▶ This is how he describes the first register: it is “the association of the signs of the zodiac with the months and the seasons, which inscribes the passage of time in a rhythm that punctuates both the cycles of the cosmos and those of nature. […] However, the association of the main constellations and planets with different parts of the body, with the temperaments or the destiny of individuals, frequent in the almanacs of the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern era, has disappeared. 19th-century publications.” This precision is of extreme importance for the subject that concerns us here, namely the possible impact that social artefacts would have according to Geoffrey Dean on the Gauquelin data. 19th-century almanacs generally gave no indication of the temperaments and destinies of individuals. This absence made the development of a rudimentary genethliac astrology almost impossible. For it to have been able to do so, these populations would have had to have access to scholarly astrology manuals, which was not the case. Baubérot rightly concludes that “The almanac would thus testify to a partial renewal of popular rural cultures: the zodiac would remain a repertoire of signs allowing us to understand the passage of time and the cycle of nature on the scale of a year, but it would have ceased to to be a key to identifying correspondences between terrestrial life and the cosmos.”

▶ The second register is that of belief in astro-meteorology: “The belief in the influence of the stars, and especially the moon, on the evolution of time is both ancient and deeply rooted in rural popular culture. Almanacs sometimes make use of this when they associate their prognoses with the phases of the moon, or even make them the causes of weather variations.” Note that astro-meteorology has nothing to do with individual astrology. It is aimed at agricultural utility, not psychological, “characterological”. “In most cases, the almanacs content themselves with forecasting the weather without worrying about justifying the variations. […] The meteorology of the almanacs could then respond to an expectation which would be less based on ancient beliefs than on the growing desire, on the part of a rural world which is gradually rationalizing its methods of agricultural production, to have access to a way to predict the weather.”

▶ The third register, finally, considers the astrology of almanacs as a kind of literary or romantic genre: “it is possible to put forward the hypothesis that the presence of astrology in the almanacs stems from the register of the imagination and distraction. Indeed, there is nothing to indicate that readers believe the weather forecasts offered to them to be true. The reading of these pages can be distanced, integrate a part of the game and encourage the reader to check, a posteriori, the accuracy or not of the forecasts. The expression ‘liar like an almanac’, which even inspires the title of certain publications, […] suggests that this remote reading can be the object of an implicit connivance between the publisher and the reader. The chapters of prophecy particularly lend themselves to this interpretation. Their impersonal and stereotyped tone never announcing precise or localized facts, can offer support to the imagination, to daydreaming.” Almanacs no longer exist, but horoscopic headings have replaced them in most popular (or not) newspapers. Very few people believe the nonsense they tell, but very many are still those who cast an amused (or more rarely interested) eye on the predictions concerning their Sun Sign or that of their loved ones. Presumably a very large number of almanac readers did the same, not caring in the least what Geoffrey Dean would conjecture about them a century or a century and a half later.

In conclusion of his very documented study, Arnaud Baubérot writes that “Finally, the astrology of the popular almanacs of the 19th century does not present itself as an established system for predicting the future any more than it invites the reader to believe positively in the possibility of reading the future in the stars. It is more like a literary genre, a rustic form of anticipation literature, with its own codes, its own style and its recurring characters; a genre that aims to arouse the curiosity of the reader to stimulate his imagination, his fears or his hopes, or more simply to distract and amuse him. Its success is based both on the wide dissemination of the proto-mass media that carries it, and on the fact that it mobilizes a repertoire of signs – the zodiac, the major figures of astrologers, prophetic emphasis… – which refer to a mode of representation of the world which tends to disappear, but whose signifiers still find an echo in popular rural culture.” And he’s right. From this point of view, this form of popular astrology was only one element among others of a more general anticipatory narrative that overflowed it on all sides and within which it was drowned.

Let us now return to the social artefact questioning the Gauquelin data, whose plausibility Geoffrey Dean justifies by the cultural significance of astrology in the almanacs of the 19th century. You will have to temporarily put everything you have just learned about this popular literature in brackets, because this frenzied anti-astrologer has a completely different vision of almanacs, which can be described at best as very oriented, ad hoc, and at worst fraudulent, even charlatanesque. Let’s go.

▶ On the sole basis of 56 European and American almanacs that he consulted (while in France alone, there were about 400 different ones around 1850), Dean assessed that most of them gave the positions of the Moon and the Sun as well as the dates of the entry of the Sun into the Signs of the zodiac, that a third gave the Aspects of the Moon with the planets at astro-meteorological purposes and another third the times of planetary sunrise, sunset and culmination, these two thirds overlapping.

For the latter, the criterion used was that of the visibility, so for the the verse the presence of the planets in House XII, “key sector” Ascendant of Gauquelin, which Dean says would largely explain the anomalous frequencies in this sector. But he omits to point out that the same criterion should then produce abnormal frequencies in House VII (zone of the sunsets visible planets), while the Gauquelin statistics show these frequencies in House VI below the horizon (so when the planets are no longer visible) and not at all in House VII. One also wonders why, in this hypothesis, the cheating populations concerned would have decided to give birth to their offspring approximately one to two hours after the upper and lower culminations at the meridian (“Culmination meant something at its highest power, just as ‘the culmination of our efforts’ does today”, notes on this subject Geoffrey Dean) rather than at the exact moment of these culminations. And concerning the excess frequencies near the lower meridian (Imum Coeli), one also wonders why these cheating populations would have declared births favoring planets at their midnight, while they are then absolutely invisible… and that midnight is a time beloved by witches, and therefore in principle unloved by peasants. Dean’s argument only holds for rises and partially for upper culminations, which means it’s worthless.

▶ These almanacs, which had essentially an agricultural and religious calendrical vocation and very incidentally and rudimentary astrological vocation, were especially popular in the rural settlement areas, then in the majority. One can imagine without much probability of being mistaken that these rural populations, for the most part poorly educated or even illiterate, cared little about checking the planetary positions in their local sphere. Only those who knew how to read could vaguely specify them — if however the almanacs mentioned them, which was the case only for a part of them — to all those who did not know it, insofar as some the others were not too busy working in the fields to worry about this kind of scholarly considerations. You have to be an obsessive anti-astrologist of the 20th century to have such anachronistic ideas.

▶ We have seen previously that the argument of the visibility criterion was inadmissible. Another hypothesis remains to be tested, that of the impact of theoretical astrological beliefs. From this point of view, the absurd hypothesis of attribution by “perinatal control” parenting based on almanacs is also anachronistic. Indeed, during the relevant period, almost all astrologers based themselves (among other criteria) on the “Angular houses” as defined by Ptolemy in his Tetrabiblos to assess the planetary powers. Gold the extents of these Ptolemaic Angular Houses coincide only very partially or not at all with the “key sectors” by Gauquelin. To please the obsessive anti-astrologism of Geoffrey Dean at the beginning of the 21st century, it would therefore have been necessary for the majority of the astrologers of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century be aware of the results of the Gauquelin statistics conducted during the second half of the 20th century. Poorly educated or illiterate rural populations should also have been aware of this providential anachronism. And this while having the astronomical and mathematical knowledge allowing them to calculate the ecliptic latitudes of the planets below the horizon, whereas the almanacs provided the best information (when they did, which was rare) only on imprecise ecliptic longitudes.

▶ For such a hypothesis of attribution by “perinatal control” parental had the slightest probability of having affected the Gauquelin statistics anyway, despite its charlatanesque and anachronistic absurdity, to the point of invalidating the results, it would also have been necessary for archival documents to attest that between 1800 and 1950 would have existed a profound and generalized reform of the astrological tradition bearing on the redefinition of the Ptolemaic zones of angularity. This tradition should have been omnipresent in Europe and therefore cross the linguistic borders between the countries that constitute it. It should even have crossed the Atlantic Ocean and spread throughout North America, given the many replications from local population samples made by US anti-astrologists. However, no archival document — and they are very numerous — attests to the existence of this type of vast reform. What would come closest to it are the works of Choisnard at the beginning of the 20th century, which had only a confidential and French-speaking diffusion in very restricted astrological circles, the conservative majority of the majority of the French astrologers who had been informed of them being hostile or indifferent to them.

▶ For this absurd, unverifiable, anachronistic and grotesque vicious circle anti-astrologer concocted by Geoffrey Dean for the sole purpose of ruining astro-statistics Gauquelin does not contain even an ounce of reality, it would of course also have been necessary for the European and American rural populations, mostly uneducated or illiterate, to have been aware of this great transcontinental astrological reform that never took place. And whose proven non-existence, of which they could not be aware, would nevertheless have encouraged a significant percentage of them to have the false birth times of their offspring registered with the civil registry. A sufficient proportion to invalidate a century to a century and a half later the results of Gauquelin statistics by magically transforming hypothetical planetary influences into attributions by “perinatal control” proven parenting.

▶ We see that none of Geoffrey Dean’s arguments hold water. The planetary visibility argument applies only to their risings, and that’s it. It is therefore specious. If he wasn’t ad hoc, we should observe in the Gauquelin statistics an excess of planetary frequencies in House VII, which is not the case. And we saw that if the cheater populations had relied on the planetary transits at the meridian (which only about a third of them could possibly have known about), they would probably have “decided” of “choose” the upper and lower culminations about exact. Which would have caused, in the Gauquelin statistics, abnormal frequencies around the Midheaven and the Imum Coeli, and not about one to two hours after the passage through the meridian as is the case. The arguments of visibility and culminations are therefore worthless. And in this case, the only other possible hypothesis is that of the knowledge by these cheating populations of the reform of the post-Ptolemaic Houses, which is also worthless.

▶ If the time frauds were as important as Dean suspects in supporting his conspiratorial mania, the vital records should have included a significant number of very precise birth times down to the minute. Indeed, those of the almanacs providing information on planetary sunrises, culminations and sunsets mentioned the precise hours and minutes of these phenomena. But we don’t see anything like that. If a large number of parents cheat on the time, why would they have done so by rounding it off when the almanacs at the origin of this deception gave the precise hour and minutes?

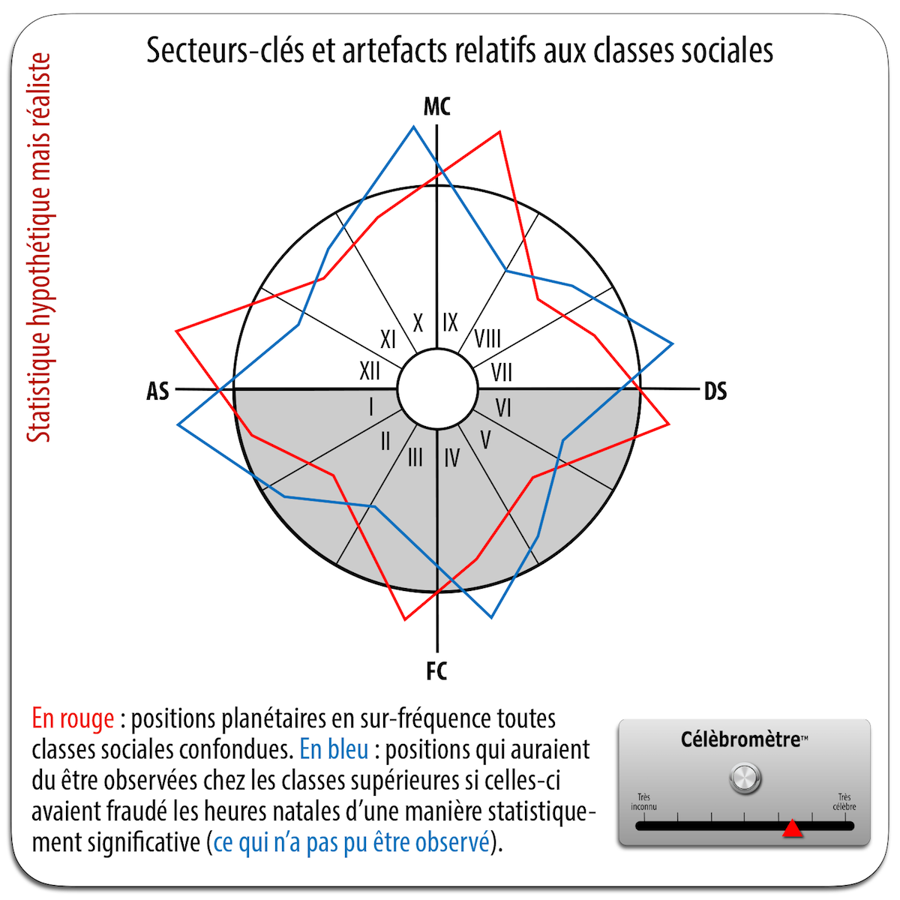

▶ A final argument will complete the ruin of pseudo-attributions by “perinatal control” parent of Dean. He is kind conditionalist and deals with the different professions concerned by the Gauquelin statistics. These can be classified into two groups: that of professions with a dominant “physics” (athletes) and dominant “intellectual” (actors, deputies, generals, writers, scientists and priests). It has been proven that a large majority of those who become “champions” Athletes came from the lower social classes of society. Not because they would be more gifted for sport, but because most sports do not require professional success to have a priori a relational network, a socio-cultural level and high financial means. It is exactly the opposite for the upper social classes, in whose offspring the professions of “champions” intellectuals are over-represented. Moreover, between 1800 and 1950, these upper classes were overwhelmingly urban.

▶ However, it was precisely these upper classes, generally well educated, who could have access to the knowledge of scholarly astrology, and more precisely the very small fraction of its members who were interested in this kind of subject. Logically, it would therefore have been in the offspring of these favored classes, therefore among the “champions” intellectuals, that the most numerous frauds on the hour and/or day of birth could have been observed. And for these frauds to have had any influence on the Gauquelin statistics, it would also have been necessary for these privileged people to have also been aware of the great post-Ptolemaic reform which never took place in their time. In what way these urban upper classes were on an equal footing, from the point of view of ignorance of a non-existent event, with the lower classes. However, Geoffrey Dean has not produced the slightest statistical study to test this conditionalist hypothesis, which alone could confirm or invalidate his assertions as to the determining role of these social artefacts. It follows that these statements are only opinions.

▶ It should also be noted that in the 19th century and during the first third of the 20th century, i.e. the reference period of the Gauquelin data, astrology had fallen into disuse among the European upper social classes. Since the Age of Enlightenment and the advent of scientific materialism, it was considered by these classes only as a medieval superstition unworthy of their level of education. Publications of learned astrology were then very rare and reserved for a minority, who alone had the financial means to pay for the services of the few learned astrologers who remained in the cities at that time.

▶ Admitting that a tiny proportion of these members of the upper classes had nevertheless defrauded on the birth times of their offspring for astrological reasons, these frauds would therefore have been based on the doctrine of angularities transmitted by Ptolemy, which alone was authoritative. They would therefore have had the consequence of encouraging children to be born at times during which the planets considered to be dominant were in Houses I, X, VII & IV. And in this case we would have been able to statistically observe an over-frequency of planets in these Houses in relation to the corresponding professions (so all except sports). But nothing like this appears: the “key sectors” Gauquelin are pretty much the same for all professions.