Your Planets

Portraits of the Planets

Aspects between Planets

The planetary ages

The planetary families

Planets in Signs

The Planets in comics

This long study on the world according to Claude Ptolemy was written in counterpoint to the series of video animations in four episodes which follow it and which deal with the same theme, but in the language of images. This text sheds light on these educational animations, both astronomical and astrological, by giving them a historical and epistemological perspective that images alone could not trace.

From the early central Middle Ages (12th century) to the Renaissance (15th-17th centuries), Europe is rediscovering ancient Greek sciences and knowledge, ignored or lost sight of for a very long time, through the Latin translation of texts from the muslim scholars and Byzantines who had ensured its transmission.

Two major characters then emerge, eclipsing their innumerable predecessors in their fame: Aristotle (– 4th century) and Ptolemy (+ 2nd century). As almost always in antiquity, their respective knowledge concerned many areas of theoretical and practical knowledge, from physics to metaphysics included. However, the work of Aristotle was above all that of a philosopher and a thinker embracing all fields of knowledge, while that of Ptolemy was more that of a scientist seeking to elucidate the physical laws of nature.

Among this rediscovered Hellenistic knowledge were astronomy and astrology to which Ptolemy, both astrologer and astronomer, had devoted two works, the Almagest for astronomy and Tetrabiblos for astrology. Both then became the dominant references in their respective fields until the end of the 17th century, i.e. for a period of about 1500 years from their first publication and 500 years from their rediscovery.

On the subject of astronomy, Aristotle and Ptolemy only agreed on three points: the universe was geocentric, the Earth was stationary, and the orbits of the Sun, Moon and planets were perfectly circular. that they were both wrong, as was formally demonstrated by Johannes Kepler in the 17th century. On all other points their conceptions were divergent and irreconcilable. Aristotle’s theoretical system was indeed so remote from what could be observed that Ptolemy, following Hipparchus who discovered the precession of the equinoxes and of which he was a faithful successor, was obliged to reform it radically. These were therefore the methods of calculation and the astronomical conceptions exposed in the Almagest (whose original name is “Math syntax”) which were adopted by European scholars from the Middle Ages, and not those of Aristotle.

From a more philosophical point of view but still concerning astronomical theories, the conceptions of Aristotle and Ptolemy also diverged very strongly.

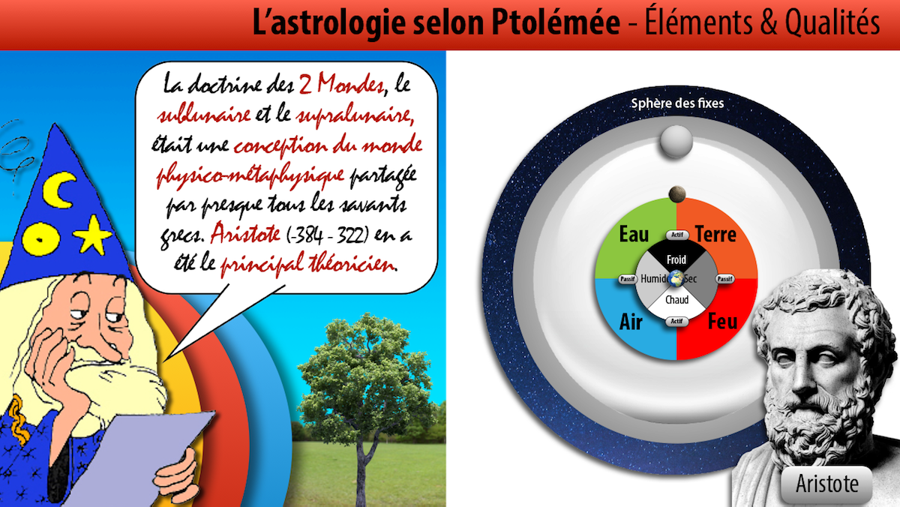

For Aristotle, the universe consisted of two concentric and mutually sealed spheres, the exact center of which was that of the Earth. The first constituted the sublunar world, including within the lunar orbit the Earth and its atmosphere. It was the place of permanent change and imperfection and ruled by the 4 Elements Earth, Water, Air and Fire in perpetual change. The second constituted the supralunar world, including the Moon, the Sun, the planets and the stars, the latter being considered as fixed. This world was for Aristotle that of immutability and perfection, reflections of the divine nature of the cosmos. Between these two worlds there was separation: the Moon, the Sun and the planets which revolved inside the 55 interlocking crystal spheres that Aristotle had imagined beyond the 3 spheres of Water, Air and Fire which enveloped the terrestrial sphere could have no direct influence on the terrestrial, aquatic, aerial and igneous metamorphoses of the sublunar world and its inhabitants, with the exception of course of the Sun whose effects it was difficult for him to ignore. All the more so since these stars were not (especially not!) made of Earth, Water, Air or Fire but of an etheric matter whose nature Aristotle did not specify. From these conceptions it followed that Aristotle was against astrology.

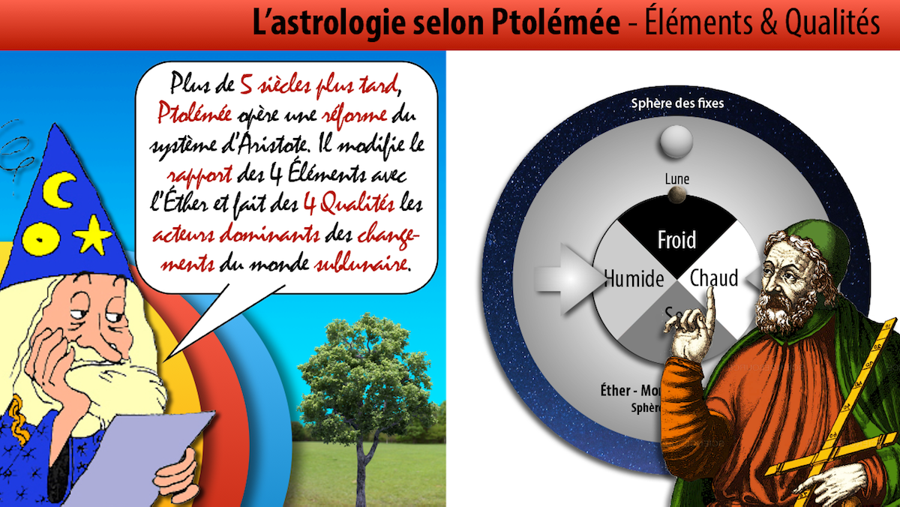

Ptolemy’s conception was quite different. For him, the border between the sublunar and supralunar worlds was not watertight, since both participated in the same cosmic unity. The planets were not enclosed in crystalline spheres but described immaterial orbits in a fluid ether, and the fixed point around which their rotations took place was located outside the terrestrial globe. The stars had a direct influence on the sublunar world and its inhabitants through the intermediary of the 4 fundamental physical qualities which were hot, humid, dry and cold that they shared with him. Finally, the humidifying effects of the oceans and the terrestrial atmosphere extended for him to the orbit of Venus, thus well beyond the lunar border. Ptolemy does make a brief (required?) reference to the Aristotelian elemental spheres at the very beginning of the Tetrabiblos: “Fire and air are surrounded and moved by the movements of the ether; and fire and air in turn surround and move everything else: earth, water, plants and animals” (Book I, 2.). But in his long demonstration of planetary influences which follows, he effectively eliminates the sphere of Fire, incompatible with his conception of the humidifying effects of Water and Air: its existence would have had the effect of vaporizing the humidity specific to the latter before it reaches the orbit of Mercury and then that of Venus. The scholar from Alexandria was not a yes-man of Aristotelian dogma.

Let us now move on to the relationship between Aristotle and Ptolemy with astrology itself. If the astronomical and cosmological conceptions of one and the other diverged strongly, their respective opinions about astrology were diametrically opposed: Aristotle was against and Ptolemy was for.

In this case it is customary to think, among exegetes anachronistically hostile to astrology, that Aristotle’s opinion on this subject was the fruit of his very great rationalist wisdom of very eminent philosopher always studied in universities. Conversely, the fact that the very great astronomer that was Ptolemy was coupled with a very great astrologer passes, according to the same people, for a kind of incongruity, of irrationalist deviation of an eminent spirit, whose study of heretical thought does not cross fortunately very rarely the doors of the amphitheaters of official knowledge.

The reality is different. In this matter, Aristotle’s opinion was based only on metaphysical and spiritualist presuppositions, while Ptolemy’s arguments were those of a scholar who considered astrology to be a natural science. But before exposing this matter, let’s contextualize a bit to illuminate these opposing worldviews.

When Aristotle emits au – 4th century his opinion unfavorable to the influence of the stars, the greek philosophy has only two centuries of existence, during which it has gradually and laboriously conquered its status as a discipline of autonomous thought distinct from both religion and the so-called natural sciences. But at the very time when Aristotle was trying to impose on the human mind the laws of deductive reasoning which, he believed, would make it possible to put an end to ancient beliefs, the powerful wave of Babylonian astrology-astronomy, mixed with superstitious Egyptian astrolatry, swept over Greece and aroused great enthusiasm. Worse still, she is one of the fruits of the conquests of one of her students, namely Alexander The Great ! However, it should be noted that at – 5th century, that of Pericles, astronomy and astrology were still unknown in Greece.

This astral craze obviously aroused many vocations of prophets and crooks who were sellers of the future, while the most learned minds set about the task of rationalizing Chaldean astrology bastardized by Egyptian superstitions to make it compatible with the canons of Greek thought clearing its way towards rationality. In this historical-cognitive context, we can partly glimpse one of the reasons for the condemnation of Aristotle, even if it is not the most decisive: as always, most of those who claimed to be the depositaries of astrological knowledge n were only usurpers and profiteers of the credulity of the masses.

When, on the contrary, Ptolemy argues in 2nd century in favor of astrology, the historical-cognitive context has changed. Hellenistic astrology-astronomy was born, carrying its share of rare great scholars and multiple charlatans and, in the Roman Empire of the 1st century, we are witnessing a real astromania. In a context of generalized astro-quackery, pro- and anti-astrology scholars tore each other apart against a background of popular astrolatry, so much so that the Emperor Tiberius, who knew astrology quite well and was rather favorable to it, ended up by doing expel from Rome all “Chaldeans” (this was the common name for astrologers) and prohibit the dissemination of astrological works and the consultation of astrologers. This measure having proved rather ineffective, another emperor again ordered, in the year 52, the expulsion from Rome of all astrologers, with the exception of those who were genuine scholars and/or who were in good health. court in Roman high society.

At 2nd century therefore, the Roman astromaniacal wave has died down even if the astro-charlatans still abound. From 117 to 180, under the enlightened reigns of the emperors Hadrian, Antoninus and Marc Aurelius, Hellenism flourishes again in Rome, and with it a learned astrology which regains its letters of nobility. It is in this context that Ptolemy was born in Thebes, Egypt at the end of the 1st century and that he spent most of his life in Alexandria, a city founded in the year −331 by Alexander the Great, a pupil of Aristotle. Although a Roman citizen, this Greek probably never set foot in the capital of the empire. From an intellectual point of view, he lost nothing: Alexandria was then one of the greatest Hellenistic cultural centers in the Mediterranean. Admittedly, a considerable number of manuscripts of his famous library probably went up in smoke during a fire around the year −50, probably depriving Ptolemy of many ancient Greek texts or texts translated into Greek; but because of its geographical position, it was in direct contact with the Chaldean and Egyptian astrological traditions.

If we know with certainty only the main lines of the life of Aristotle who was extremely famous and adored in his time, on the other hand we know absolutely nothing about that of Ptolemy who seems to have voluntarily erased himself behind his work. This is made up of two major works, the Almagest, treatise on astronomical calculations and catalog of stars and constellations resuming and improving the work of Hipparchus, and the Tetrabiblos, a kind of encyclopedia of astrology where he exposes the theories, beliefs and traditional practices augmented by his own conceptions and discoveries. He criticizes there as ruthlessly as Aristotle the delusions, superstitions and other charlataneries of the majority of ancient and contemporary astrologers and pseudo-astrologers but, unlike Aristotle, his criticisms are those of a convinced man of the art who is sorry and rebels against the actions and ideas of those who usurp this function or are not up to it.

One might think that Aristotle’s opposition to astrology was the result of a rational reflection based on what he knew of the laws of nature, reflection which would have led him to doubt the possibility of an influence stars on living beings and terrestrial objects. However, it is not. Aristotelian anti-astrologism is in fact based on a Platonic metaphysical presupposition.

For Aristotle, in fact, astrology is “A tradition coming from the most remote antiquity and transmitted to posterity under the veil of the fable [which] teaches us that the stars are gods and that the divinity embraces all of nature; all the rest is only a fabulous story imagined to persuade the vulgar and to serve the laws and common interests. Thus the gods are given the human form, they are represented under the figure of certain animals; and a thousand inventions of the same kind which are connected with these fables.”

here’s one peremptory and lapidary judgment which would not be out of place in the vocabulary of a member of the Rationalist Union. In this writing, Aristotle effectively condemns without appeal not only astrological fabrications and superstitions, but also astrology itself. But this anti-astrological text has a second part that has absolutely nothing to do with the reasons and unreasons of modern rationalists.

“If we separate the principle itself from the narrative”, continues Aristotle, “and if we only consider this idea, that all primary essences are gods, then we will see that this is a truly divine tradition. An explanation which is not without probability is that the various arts and philosophy were many times discovered and many times lost, as is very possible, and that these beliefs are, so to speak, remnants of ancient wisdom, preserved to our time. Such are the reservations under which we accept the opinions of our fathers and the tradition of the first ages.”

Translation: the astrological narrative is indeed a vulgar deception and the belief in the influence of the stars an error, but the idea or principle underlying them is fundamentally correct and true, although it has been altered over the years. millennia by the decadence of a wisdom of an original tradition “truly divine”. Indeed Aristotle, like Plato, identified theology with astronomy and maintained that the mobile stars, rotating on the surface of their crystal spheres in the perfect, incorruptible and immutable ether, had souls which reflected the principle of the first and immobile divine motor.

In this perspective, the astrological-metaphysical idea according to which “all prime essences are gods” could only suit Aristotle… provided that it is rid of the whole narrative and of the astrological reality that coats it, that is to say, reduced to a pure metaphysical instance. Because if the stars had a direct influence on the sublunar world, that would mean that the latter is permeable to the supralunar world, which would ruin a fundamental dogma of the Aristotelian conception of the world… Nothing to do with the anti-astrological and pseudo- zetetic of the Rationalist Union, scientistic sect born in the 20th century. In short, for Aristotle, the stars were agents of the divine (even if the latter was for him the “god of philosophers”) who cannot compromise themselves with the corruptions and changes of the imperfect sublunary world impervious to their influence. And this is how Aristotle, while posing as a despiser of astrology, thought as a true astrolater.

Aristotle does not seem to have taken the trouble to seriously study astrology before condemning it so lapidarily and with such grotesque arguments. Otherwise, he would not have written this text about this knowledge. It can therefore be said that he did not know what he was talking about and that the astrolatric reasoning on which his conviction was based did not hold water. Moreover, the astronomical system he had imagined had only a very distant relationship with the observation data of the movements and positions of the stars.

Both astronomer and astrologer, Ptolemy knew what he was talking about and, unlike Aristotle, he benefited from the continuous progress of astronomy, mathematics and astrology since the latter’s death. No trace of paraphilosophical astrolatry in him. In his mind, the stars are not divine primary essences, but material celestial bodies orbiting around points which can only be external to the center of the Earth if we want the theory that we make of their movements to correspond to the observations that we can make of them.

In the introduction to Book I of his Tetrabiblos, he clearly lays out the difference between astronomy and astrology, and he does it in the most rational way: astronomy, “the first, by rank and efficiency, allows us to know the relative positions that the Sun, the Moon and all the planets will adopt at any time between them and with respect to the Earth, due to their movements”; astrology, “the second, by analyzing the natural characteristics specific to these relative configurations, makes us detect the changes they cause in the ‘content’ they encompass”.

But if he exposes this difference, he immediately operates the link which he considers as quasi-organic between the two: in the Almagest, “I exposed […] in the most demonstrative way possible the first of these methods, which has its own theory and which is valid by itself. However, its results cannot compete with those obtained by combining it with the second.”

Ptolemy then warns that the second method (astrology) is “not “not as autonomous as the first” (astronomy). Indeed, it depends on other multifactorial influences specific to earthly things and beings. He therefore considers it necessary to issue a second warning: “whoever has the search for truth at heart will have to avoid what the mind can grasp by this second method with the unalterable and sure knowledge that the first offers”. Translation: for him, astronomy is about the absolute, the simplicity and the predictability of mathematical certainties determining the course of the stars, and its astrological effects of the conditional, probabilities, diversity and complexity of living things.

Indeed, writes Ptolemy, “It is certainly the difference between seeds that has the greatest influence on species specificity. If, at birth, the all-encompassing sky and the horizon are the same… each type of seed prevails by impressing its appropriate general pattern: here a man, there a horse, and likewise for every other living being.” And within the same species – in this case, the human species – it does not fail to underline the need to take into account the diversity of the places of birth which “are also at the origin of the differences which are far from being negligible between the creatures […]. Finally, when all these conditions mentioned were the same, education and morals do not fail to determine in part the individual course of a life.” Translation: astral influences are only exercised within the determinisms specific to each species and to the various human socio-cultures, and their expression is therefore conditioned by these.

Ptolemy thus exposes clearly the line of demarcation between what it is agreed to call since the 20th century the “hard sciences” (e.g. astronomy and mathematics) and “soft sciences” (like all the sciences say “human”). But at the same time he defines astrology, not as a “human science”, but as a knowledge located exactly at the articulation between “hard sciences” and “soft sciences”, which gives it a very special status and makes its study extremely complex.

It also draws another line of demarcation: that which separates the fatalistic prediction of the conditional forecast: “Let us avoid believing that everything that happens to men is the effect of a cause coming from above as if, from the beginning, according to some irrevocable and divine decree, everything had been regulated in advance for each individual and happened out of necessity, without any other cause being able to prevent it. In truth, if the movement of the celestial bodies is accomplished from all eternity by virtue of a divine and immutable destiny… the change of earthly things is, for its part, subject to a natural and variable destiny, drawing its first causes by chance, or by way of natural consequence.” Translation: the sky is a transmitter which proposes but does not impose everything, and man is a receiver who disposes but can also propose original responses to celestial proposals, within the framework of his earthly conditioning.

The apprehension of this complexity inherent in astrological knowledge is not within the reach of everyone and even less to that of anti-astrology who don’t know what they’re talking about. Indeed for Ptolemy, the one who seeks to understand the astrological fact “should not take the fragility and complexity of such a study as a pretext, nor the difficulty in apprehending the matter in its qualitative dimension, to shrink from such an investigation, since the observation of most of the events, and most universal, makes it clear that they derive their cause from the all-encompassing heaven.”

Here Ptolemy grants the stars of the solar system an influence of a magnitude that appears to be clearly exaggerated for modern scholarly astrology. But if we compare his words with those of the majority of astrologers of his time who believed in absolute astral conditioning leading to blind fatalism, he is remarkably moderate. We must always be wary of anachronistic judgements.

Fifteen centuries later, another great astronomer-astrologer, Johannes Kepler, will confirm this conditional character of astrological determinism: “The sky acts on man during his life like the strings that a peasant ties randomly around the gourds of his field: the knots do not make the gourd grow, but they determine its shape. Likewise the sky: it does not give man his habits, his history, his happiness, his children, his wealth, his wife, but it shapes his condition.”

Regarding quotes, two clarifications: the famous Latin phrase “astra inclinant, sed non necessitant” (“the stars incline but do not require”) and all its various variants is very often attributed to Ptolemy and sometimes to Thomas Aquinas. But we do not find it anywhere in their writings. Another quote, “vir sapiens dominatur astris” (“the wise rule the stars”), widespread since the 13th century, is also very frequently attributed to the same two, and sometimes also to Albert the Great. It is not found in their works either.

This is of no importance on the merits, since these two sentences express very well, in striking shortcuts, what the three of them thought.

Having clearly defined the character conditional, relative and probabilistic astrological knowledge, Ptolemy issues a final warning: “Anything that is difficult for the multitude to understand easily lends itself to calumny. And if only the blind could object to the first science (i.e. astronomy), the second could fuel easy accusations; either because the complex problems it poses in several places suggest that it is incomprehensible in its entirety, or because the difficulty we have in protecting ourselves against events known in advance has discredited the very purpose of this study, making it considered superfluous.”

Ptolemy is much more ruthless than Aristotle with the impostors of astrology, on the one hand because he does not confuse them with the true scholars of this discipline, and on the other hand because his criticism is not based, like that of Aristotle, on metaphysical prejudices but on factual findings: “Many profit-seeking individuals deceive the layman by practicing another art under the guise of astrology; they deceive those who consult them by pretending to make many forecasts, even on questions which, by definition, do not come from any foreknowledge, and thereby offer the most informed minds an opportunity to condemn all forecasts without discrimination, including those that are inherently formulable. But such a condemnation is not admissible: there is no need, in fact, to abolish philosophy because some who claim to be philosophers behave like charlatans.”

This last sentence was obviously not aimed at Aristotle… even if one can consider that his opinion on astrology was a kind of pseudo-philosophical quackery, in that it was based on nothing other than unverifiable metaphysical presuppositions and the call for a hypothetical primordial golden age knowledge that never existed.

The Aristotelian doctrine sank into oblivion upon the death of its creator. It was not taken from it until about 400 years later, in the 1st century of the Christian era, when the philosopher Andronicos of Rhodes reissued them. But the influence of Aristotle remained discreet, given that the intellectual world of the Roman Empire then preferred Epicureanism or Stoicism or even the neoplatonism, a more mystical than philosophical mixture of the philosophies of Plato, Pythagoras and Aristotle sprinkled with oriental spiritualities.

A century after Aristotle’s work reappeared, Ptolemy wrote his own, and what was later to become the Church began to form. The fate and posterity of these two antagonistic conceptions of the cosmos will long be linked to the rise of Christianity and determined by the positioning of the Church vis-à-vis them. Indeed, religion gradually became an important vector in the life of ideas and, when it was proclaimed the state religion of the Roman Empire, its hegemonic position enabled it to impose its standards of thought instead of those philosophers and other religions.

Original Christianity did not appear in the Vatican. It was born and first developed in the Eastern Roman Empire. That is to say in the Middle East, Mesopotamia and Persia, regions where the influence of astrological beliefs and knowledge was extremely significant, given that it was there that they had appeared millennia earlier. The first Christians, especially if they were non-Jews, were therefore very open to astrology, which for better and for worse was part of their cultural landscape.

The astrological question and that of geocentrism thus formed part of the concerns of the first Christian clerics. They had to position the stammering guns of their new faith in relation to the influence of the stars and coordinate the biblical geocentrism with that of the Greek philosophers and astronomers, who were very often at the same time astrologers or astrologers.

The embryonic Church shared with Aristotle and Ptolemy the same geocentric tropism, even if the latter did not have the same source. For the Church, geocentrism was purely metaphysical and the fruit of biblical revelation; for Aristotle, it was astronomico-metaphysical and a consequence of philosophical-scientific reflection on nature; as for the geocentrism of Ptolemy, it was quite relative since for him the geometric-mathematical center planetary orbits was eccentric in relation to that of the Earth even if, good prince (astrologers, of course, since such became his nickname), he admitted that the Earth was nevertheless the center of the cosmos. These geocentrisms of different origins were therefore both complementary and in competition for the nascent Christian theology.

The determining omnipotence of the biblical god also competed for the first Christian thinkers with astral determinism, whether the latter be considered absolute (this was the opinion of most astrologers), relative and conditional (this was Ptolemy’s point of view) or non-existent in the sublunar world to which the Earth and its inhabitants belonged (this was Aristotle’s anti-astrological thesis). The question then was: the biblical god having created the cosmos, was the belief that cosmic cycles and rhythms permeated the lives of humans consistent with his will and purposes, or was it a belief that wrote against them? Or in other words: the free will offered to humans by the god of the gospels was it compatible with astral determinism, whether it was considered relative or absolute?

The educated and learned clerics of the nascent Church were therefore divided between those who, like Aristotle, were hostile to astrology for metaphysical reasons, and those who, in the wake of Ptolemy, were favorable to it provided that the influence of the stars respected free will and did not interfere with the divine will. The astrological question therefore occupied an important place in the internal concerns and disputes of the Church.

The importance of the astrological question, however, gradually faded as the assertion of a Christian theology increasingly locked in its dogmatic certainties, intolerant vis-à-vis other knowledge and traditions, and by consequently increasingly hostile to astrology, which was seen as a pagan and ungodly belief incompatible with the burgeoning new faith. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (4th-5th centuries), eminent theologian, Father of the Church and author in particular of confessions, of the city of god and of Of the Trinity, is a good illustration of this new orientation.

Indeed, this Roman scholar from Algeria was at the beginning of his life astrology enthusiast before making a 180° turn and abruptly throwing it back. This excerpt from his confessions, written between 397 and 401, illustrates this reversal well: “[True Christian piety] rejects these practices [astrology] and condemns them. It is to you, Lord, that it is good to address his confession, to say: ‘Have mercy on me, heal my soul, for I have sinned against you’; and instead of abusing your indulgence to give themselves license to sin […] To all these salutary advice, [astrologers] endeavor to strike the death blow when they say: ‘It is from heaven irresistible reasons to sin’, or even ‘It was Venus who did that, or Saturn, or Mars’, all this, of course, to exonerate man from his responsibility — who is only flesh and blood, proud rottenness – and throw it back on the Creator, on the Ordinator of the sky and the Stars.”

As if by chance (but it is not), this quasi-anathema was written only a few years after the Roman emperor Theodosius proclaimed Christianity the state religion (in 380), banned paganism and polytheism (in 392) and then put an end to the Olympic Games, which were the main religious manifestation of Greco-Roman antiquity (in 394). Pagans and astrologers were from then on the object of fierce persecution.

It can be said that Augustine had a quick and opportunistic anti-astrological reversal, given that it occurred in 386, exactly at the same time as his sudden conversion to Christianity, only six years after his whole faith new had become the state religion. He aspired indeed to leave Carthage, where he was for nine years a fervent follower of the manicheism, a religion where astrology figured prominently — and a proven astrologer. He was then teaching grammar and rhetoric there, and planned to make a great career in Rome. In this he succeeded perfectly by quickly inserting himself into the circuits of the new ecclesiastical power: in 395, he became a bishop.

Proven astrologer, Augustine? there is no doubt. Moreover, he makes no secret of it in his confessions, as evidenced by this short extract among others. He relates that one of his Carthaginian friends, Vindicianus, had raised with him the possibility that the future saint and Father of the Church becomes like him a professional astrologer: “But you, he told me, to earn your living in society, you have your profession of rhetorician, and, if you pursue this false knowledge, it is freely and out of taste, and not out of an imperious need for resources. All the more reason to rely on me on these questions that I have painstakingly studied to the point of wanting to live exclusively with them.” Admire in passing the anachronistic hypocrisy of Augustine: at the time when this exchange took place (if it is not pure Augustinian fiction), neither he nor Vindicianus obviously thought that astrology was a “false knowledge”…

His ambitions satisfied and his career made, Augustine was too literate not to rely at least partially on the Greek philosophy he had learned in his youth to develop his Christic theology, but he preferred to do this to rest on the transcendental absolutism of Plato rather than knowledge by abstraction of Aristotle. And anyway, he did not believe in the power of reason to identify the divine being. How he was an anti-philosopher: Augustine was definitely not an Aristotelian. As for Ptolemy, whose work he could not ignore, he simply refrained from mentioning him, which says a lot about his opportunistic anti-astrological turnaround: no scholar of his time and background, especially if he was like Augustine astrologing, could not ignore the Tetrabiblos…

Finally, Augustine, who all his life will have been obsessed with the astrological question, will pretend to retain only astronomy from it, and even then, only insofar as it serves as a natural basis for establishment of the liturgical calendar as evidenced by this sentence: “Many people, certainly, know the course of the Moon which serves to determine, to celebrate it solemnly, the anniversary of the Lord’s Passion.” Indeed, the day of Easter must be placed after the full moon which follows the vernal equinox. Becoming the organizer of Christian masses was well worth the equivocal and crucifying abjuration of astrology, no doubt…

Shortly after Augustine’s death, in the 5th century, the roman empire collapsed and the Christian monasteries, which housed the best and largest libraries of the time, played a leading role in the transfer of astrological texts to medieval Europe, regardless of what Augustine would have thought of them. Eight centuries followed during which the official Church, now the hegemonic cultural authority in Europe, sank into an intolerant ignorance curled up around the hard core of its theological dogmas impermeable to ancient knowledge as to any science independent of its metaphysical dictates.

During this same time, the philosophical or astrological manuscripts molded in the libraries of the monasteries and were no longer consulted except by a few secretly dissident clerics among whom the obscurities of faith had not completely extinguished the lights of the stars, of reason and of Greek wisdom.

However, astrology returned to the forefront of the Christian theological scene in the 13th century with the rediscovery of Greek knowledge, in particular through the writings of Aristotle and Ptolemy. It did not take long for theologians — and especially for Thomas Aquinas, the most important of them — to take Aristotelian thought and combine it with the Christian worldview to make it his own corpus of central knowledge, including the particularity was to try to associate reason and faith. By a cruel irony of fate, it was at the end of the same century that the Church decided, in 1298, to canonize Augustine, even though the theology of Thomas Aquinas was about to begin to supplant that of Rastignac carthaginians who nearly became a professional astrologer…

Very favorable to a non-fatalistic and non-deterministic conception of astrology, and nevertheless an Aristotelian when Aristotle himself opposed any influence of the stars, the Dominican Thomas Aquinas is a central figure in the Church of which he is one of the main teachers. This Italian, notorious astrologer, was even canonized in 1323 and, in 1962, the decree Optatam Totius on the formation of priests, No. 16 of the Council Vatican II expressly requested that the theological formation of priests be done “with Thomas Aquinas as master”.

Thomas Aquinas, fervent Aristotelian as he was in thought if not in faith, had a much more nuanced opinion on astrology than that of Aristotle and the clerics of the Church who, like the ancient philosopher, were hostile there. And unlike Augustine, he was neither a fanatic, nor a careerist, nor a hypocrite. He certainly wrote in his De judiciis astrorum (Letter on the legitimacy of the use of astrology) that need “absolutely maintain that the will of man is not subject to the necessity proper to the stars, otherwise it would be the end of free will. And without it, good deeds would not be meritorious for man and there would be no guilt in committing evil. This is why every Christian must hold with total certainty that what depends on the will of man — all human works are of this kind — is not subject to the necessity proper to the stars. This is why we can read in Jeremiah: ‘Do not fear the phenomena of heaven which the nations fear’ […] It must therefore be taken for certain that the recourse to the consultation of the stars about what depends on the will of the man is a grave sin.”

But if Thomas Aquinas thus condemned any form of astral hyper-determinism, he nevertheless remained open, unlike Aristotle, to a natural influence of the stars as evidenced by this other extract from De judiciis astrorum: “the brute force of the celestial bodies extends to the motion of the lower bodies. Saint Augustine indeed says, in the fifth book of the city of god: ‘It is not absolutely absurd to say that certain breaths of the stars can achieve physical (corporal) changes.’ This is the reason why there seems to be no sin in the case where someone resorts to the judgment of the stars to know in advance certain effects on bodies, such as a storm or serene weather, the health or weakness of a body, fecundity or sterility of fruits, and other such things which come from physical and natural causes”, or even this excerpt from his Summa theologica: “Most men are driven by their bodily impressions. Their acts therefore commonly have no other rule than the inclination imprinted on them by the celestial bodies. A very small number, the sages, govern these inclinations by reason. Also, in many cases, the predictions of astrologers come true.” Which after all was the conception of astrology that Ptolemy had, who was however not a Christian.

Thomas Aquinas nevertheless chose Aristotle, who refused any astral influence, against Ptolemy who was of the opposite opinion. He was not, however, unaware of the work of Ptolemy, as evidenced by his text In libros de Caelo et mundo. In this Commentary on Aristotle’s Book of Heaven and the World, one of his late writings, he confesses his perplexity as a crucified believer between the contradictory astronomical conceptions of Aristotle and Ptolemy. He compares the movement that Aristotle called “circa medium”, which was that by which the philosopher designated that of a celestial body, to that of a wheel which would not turn around any center whatsoever, but around that of the universe, which could not, according to Aristotle, not to be the center of the Earth. It was the same for a Christian for whom there could be no question at the time that Christ, the only son of the Christian god, was incarnated in some desolate eccentric place of divine creation.

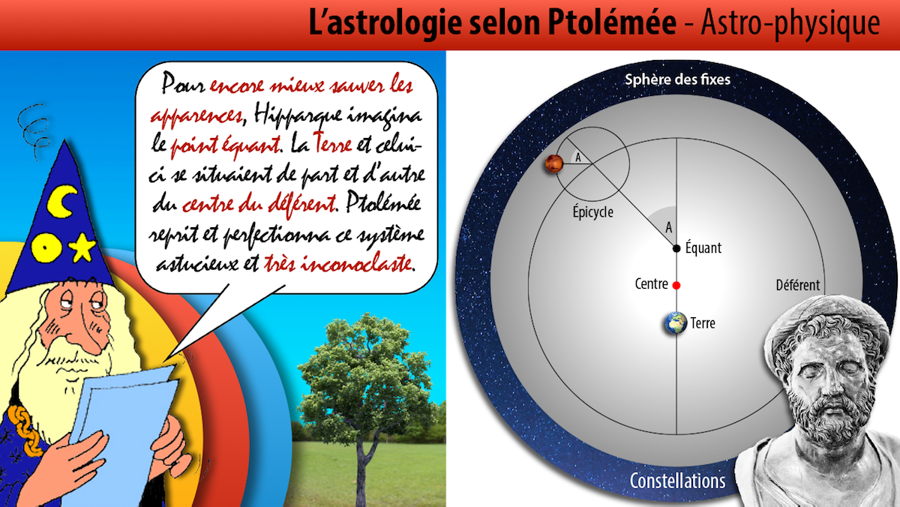

But Christiano-centered though he was, Thomas Aquinas was nonetheless a scholar and a scholar who was therefore not unaware that Ptolemy, following Hipparchus and in absolute violation of a central dogma of Aristotelian astronomy, defended a heretical astronomical theory. This claimed that the movements of the planets were determined by a equant point eccentric (and non-geocentric) around which the stars rotated in micro-orbits called epicycles, themselves grafted onto a circle called deferential. This ingenious system, based on geometrical-mathematical tricks, was the best the astronomers of antiquity had found to account for and predict the observed planetary positions.

At the end of his life, therefore, Thomas Aquinas wondered if he had made the right choice in supporting Aristotle’s astronomical system, consistent with biblical geocentric teachings but incapable of correctly predicting planetary movements, against that of Ptolemy, heretical because of eccentricity but consistent with observational data. He then wrote this absurd sentence: “Aristotle was not of this opinion”: for him, the homocentrism of planetary rotations was therefore not or no longer a demonstrated doctrine of natural science, but a simple opinion…

Here is what exactly he writes about it: “Hipparchus and Ptolemy later devised their theory of eccentrics and epicycles, to save the apparent movements of the stars. It is not a proven doctrine, it is a certain supposition. If, however, this were true, all the celestial bodies would nevertheless move around the center of the universe according to the diurnal movement, which is the movement of the supreme sphere involving the whole sky.” This text clearly demonstrates that Thomas Aquinas did not did not understand or did not want to understand how much Ptolemy’s system shook that of Aristotle, since it basically means “whatever the center, as long as there is one”. And by the way, he was making a big mistake since the direction of the geocentric diurnal motion is inverse to the real motion due to the rotation of the Earth on itself.

Faced with the Aristotle-Ptolemy astronomical dilemma, Thomas Aquinas therefore chose not to choose, like a vulgar Pontius-Pilate, which is a shame for a Christian. This may seem all the more surprising since he was a great reader of Averroes (a pro-Aristotelian Muslim physician and philosopher well acquainted with the work of Ptolemy) and Albert the Great (Dominican theologian in favor of Ptolemy), both being astrologers, the second very clearly in favor of astrology provided that it was conditional and respectful of the free will — as Ptolemy professed.

But if Thomas Aquinas made the intimate choice not to choose between Aristotle and Ptolemy, thus showing his disdain for scientific knowledge consistent with observational data, he also made the choice not to back down at the risk of denying the Aristotelianism which runs through and founds all its Summa theologica. The subjective refusal to choose is always the objective choice of a conservative option. Which does not change the fact that four centuries later, the observations of Tycho Brahe, the heliocentrism of Copernicus, the eccentric and elliptical orbits of Kepler, the telescope of Galileo and the universal gravitation of Newton will render Ptolemy’s system obsolete and will pulverize that of Aristotle.

Why did you make, you may ask, this long digression on the impact of Aristotelian astronomy and Ptolemaic astronomy-astrology on Christian theology at the end of the Roman Empire and in the Middle Ages? Answer: because at these times it was mostly high-ranking ecclesiastics who were sufficiently educated to appreciate the Greek sciences to their true extent and to disseminate them in the European cultural space. The clerics of the wealthy and influential Church were at the highest point part of the ruling class and therefore enjoyed almost absolute cultural hegemony until the Renaissance.

The concept ofcultural hegemony was founded by the Italian Marxist philosopher and theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937). It designates and describes the domination over the minds exercised by the dominant social class, through the knowledge of which it is the depository, which it creates, censors or conveys, on collective practices and beliefs. It is therefore quite adequate to understand how and why the ideas of Aristotle spread to the detriment of those of Ptolemy.

One can thus legitimately wonder whether Ptolemy’s conception of the world would not have had a completely different scope and considerable influence on Christian theology — and on the development of astrology — if Thomas Aquinas had opted for Ptolemy l astrologer rather than anti-astrology for Aristotle. Who knows what would have happened if she had been fully recognized by the Church as a acceptable natural science? It is very likely that its future in the post-christian society which began to arise from the 17th century would have been very different, since the mortgage on its hyper-deterministic and fatalistic character would have been lifted, and thus this conditional astrology design would have been diffused for at least three or four centuries, irrigating the field of collective practices and beliefs.

Indeed, it should be known that between the middle of the Middle Ages and the end of the Renaissance, astrology was commonly studied and practiced, more or less discreetly, by a large number of eminent ecclesiastics, including popes. And to do this, they could only rely on the astronomical designs and calculations of Ptolemy, which at the time were the only ones to know the planetary positions with a good margin of precision. Which amounts to saying that if theology was irrigated by Aristotle, the astrology practiced by the clerics was placed under the objective tutelage of Ptolemy.

And by the way, note that astrology as a natural science has no never been officially condemned by the Church since Augustine. The ecclesiastical condemnations brought against divinatory and fatalistic astrology, which came into conflict with the free will advocated by what would become Catholicism after the appearance of Protestantism, did not concern its approach as a natural science dealing with astral influences on bodies, minds and temperaments. On this point knowing (astrology) and believing (in a god) could agree. But we don’t rewrite history with “whether”. And when the Church gradually lost its power of cultural hegemony from the 17th century, that of Enlightenment and therefore also shadows of reason, it is the triumphant science that inherited it, giving in turn the “the” of what it is permissible to believe or not to believe. Cultural hegemony is a empty container whose contents vary over the centuries and the thoughts and beliefs they convey… but that’s another story.

As you can see, when it comes to astronomy, astrology is never far away, and vice versa. It is not easy to separate this Siamese knowledge, no offense to the Church or ignorant scientistic modernity. Thomas Aquinas had nothing against astrology considered as a natural science as conceived by the astronomer Ptolemy, but he preferred the philosophy and therefore the astronomy of Aristotle who was against it for reasons metaphysical reasons which were not exactly those of Thomas Aquinas. Understand who can and, as the latter might have confessed… “credo quia absurdum” (“I believe because it’s absurd”, quote pseudoepigraphic attributed to Tertullian, contemporary of Ptolemy, and considered the first Christian author to state his faith in Latin).

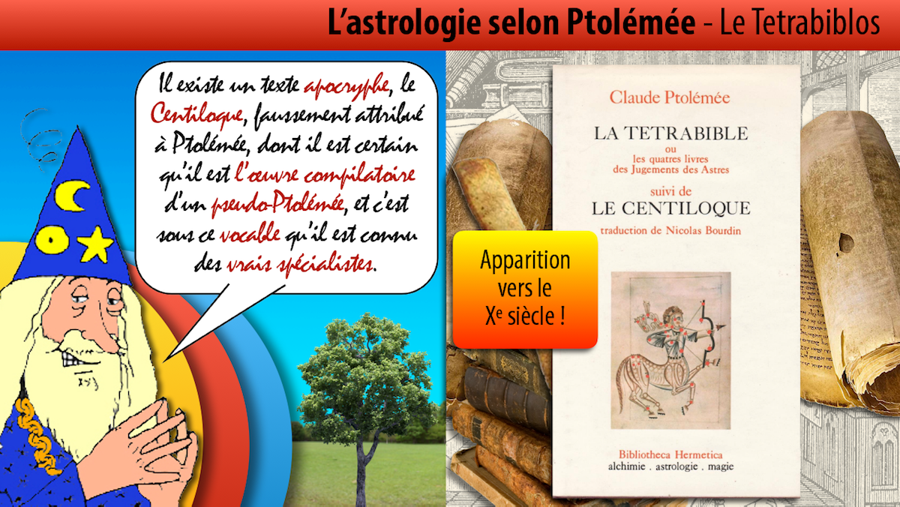

Tetra- is a numeric prefix from the Greek meaning four, and biblos means book in the same language. There Tetrabiblos of Ptolemy is therefore both a treatise and an astrological encyclopedia composed of four books (the previous hypertext link refers to the English Wikipedia file given that the French-speaking article is absolutely lamentable). First written in Greek by its author in the middle of the 2nd century, it was then translated into Arabic during the very brief intellectual golden age of islam (8th-12th centuries), following his appropriation of Greek and Persian knowledge over the course of his territorial conquests.

There is no copy of the original manuscript, but the Tetrabiblos has been frequently quoted in whole or in part by various authors over the centuries and the concordant crossing of most serious sources has made it possible to attest to its authenticity. The oldest reliable, complete and known Greek manuscript dates from the 13th century. After sinking into oblivion in the Christian West, the Tetrabiblos was the subject of various retranslations, not always very faithful, from Arabic to Latin during the rediscovery of Greek knowledge at the beginning of the central Middle Ages (12th century).

The first printed edition dates from the 16th century (in 1535 exactly). It was the work of Joachim Camerarius, a German Hellenist, who accompanied it with a Latin translation and was long considered the closest to the original text. And it was only during the 20th century that translations were made from the original Greek into other contemporary European languages, in German (1940 and 1998) then in English (1994) and finally in French (2000).

It is therefore only in the 21st century (in October 2000 to be precise) which was published for the first time, by Nil Éditions and under the curious title of Livre unique de l’astrologie, a French translation made directly from the Greek original. It is the work of Pascal Charvet, linguist, Hellenist and associate professor of classics who is neither an astrologer nor an astrologer. It is from this very recent and very scrupulous translation that most of the quotations from Ptolemy contained in this article and in the series of video animations in 4 episodes which is attached to it are taken.

The remarkable and undeniable quality of this work is attested by the astrophysicist, poet and novelist Jean Pierre Luminet, which demonstrates in the report he made on his blog that while being a very great scientist, he is neither a scientist nor a sectarian. I quote it Verbatim:

“It took until the year 2000 for the founding book of Western astrology, Tetrabiblos, to be written in 2nd century of our era by the immense scholar that was Ptolemy, is finally delivered to the public in a complete translation, made from the Greek original. This mythical work was until now known in France only through a second-hand translation which interpreted Latin versions of the text. This French translation therefore makes this book unique in its clarity and rigor, and this in a style accessible to all, desired by Ptolemy.

This book is the work of a great scientist – keen on astrology but above all astronomer, geographer, physicist, mathematician, musician and philosopher. Anxious to understand the complexity of the cosmos and to restore its unity and order, this Greek, who lived under the Emperor Hadrian, is in no way superstitious. From the first pages, he clearly distinguishes the exact science that produces astronomical certainties and the art of astrological probabilities, designating, with critical lucidity, the limits that should be set to astral conjecture. Heir to Egyptian and Chaldean knowledge, Ptolemy synthesized them to enrich the vast astrological system he proposed and which he seemed, defying time, to build for eternity. Its reading makes it possible to go beyond all sectarianism.”

The Tetrabiblos is the most remarkable, oldest, serious and exhaustive treatise on theoretical and practical astrology known. It does not date from very high antiquity, but from the middle of the 2nd century and, in that it is partly an encyclopedia of ancient astrological knowledge, techniques and beliefs, it can be considered as one of the pillars of what is commonly called the “astrological tradition”. It is therefore rightly that its author Claudius Ptolemy has been described by his peers and odd as “prince of astrologers”.

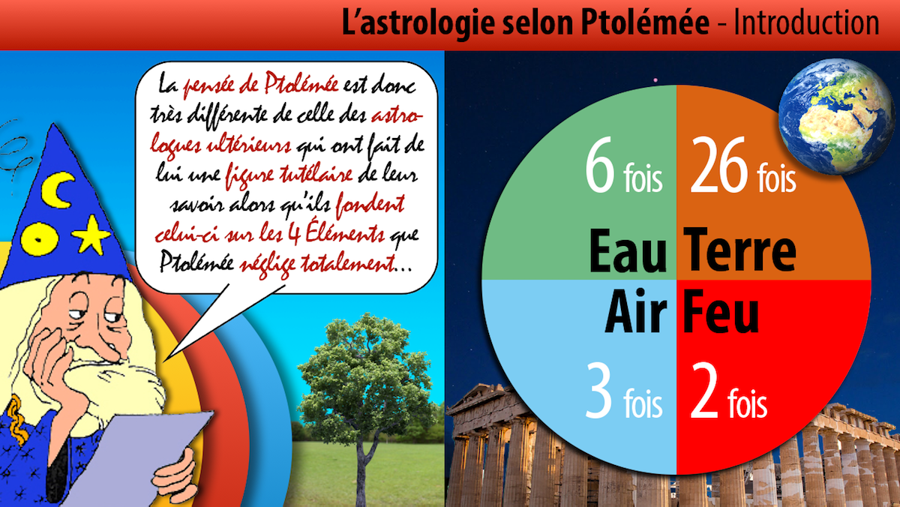

However, there is a huge misunderstanding. While the most common conception of astrology since the 16th century, and which therefore falsely claims to be “traditional”, is based to justify the influence of the zodiac and the Planets on the theoretical dogma of the 4 Elements which is one of the pillars of the Aristotelian conception of the world, we find no trace of it in the Tetrabiblos. Nowhere does Ptolemy appeal to the instances of Fire, Earth, Air and Water to found his naturalist explanation of zodiaco-planetary influences.

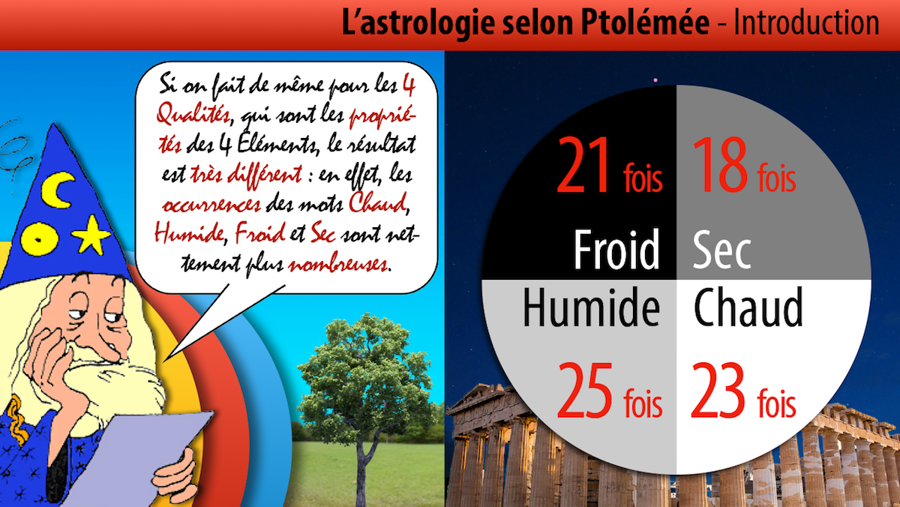

It is easy to illustrate this fact by listing the respective occurrences of the words Fire (2), Air (3), Water (6) and Earth (26) in the Tetrabiblos. Word Earth largely dominates, not because it is one of the 4 Elements, but because it is Earth which Ptolemy then alludes to. On the other hand, if we list the occurrences of the words designating the 4 Qualities, which are the properties of the 4 Elements, the result is very different: indeed, the respective occurrences of the words Hot (23), Humid (25), Cold (21) and Dry (18) are considerably more numerous. Admittedly, Aristotle also used the 4 Qualities, but by systematically associating them with the 4 Elements Earth, Water, Air and Fire, what Ptolemy never does.

From this inescapable fact, two explanatory hypotheses can be drawn: either the “astrological tradition” is absent from the work of Ptolemy, or else the dominant conception of astrology which claims the 4 Elements has absolutely nothing “traditional”. The first hypothesis being excluded, since in its Tetrabiblos Ptolemy constantly refers to tradition, it is the second that must be retained. And historical research shows that this is indeed the case.

There is indeed no reliable document from a reliable source attesting to the use of the theory of the 4 Elements in astrological texts prior to the Tetrabiblos.

The first known text mentioning the 4 Elements in astrology is from Vettius Valens (+120, +175), a contemporary of Ptolemy. He makes only a brief mention of the assignment of the 4 Elements to the 4 great trines which structure the zodiac, without developing it and without this assignment also bearing on the 12 Signs and the 7 Planets. This very mediocre astrologer probably did not imagine it himself. Later, in the 4th century, the astrologer and compiler Firmicus Maternus mentions the 4 Elements again in his book Mathesis, but from an Aristotelian philosophical point of view, and without ever linking them to the Planets or the zodiac. The attribution of the 4 Elements to the zodiac and to the Planets would therefore not have occurred earlier than the end of the Middle Ages, or even only in the 15th century with the rediscovery of ancient Greco-Roman knowledge prompted by the Renaissance. In any case, it was only from the 16th century that begins to emerge more and more frequently the conception of astrology based on the 4 Elements.

But the belief that astrology is based on the 4 Elements has become so obvious and common that even Pascal Charvet, yet author of this new translation, also succumbs to it despite the fact that he had the original Greek text in front of him. Here is what he writes in his personal presentation of the Tetrabiblos: “The stroke of genius of the astronomer was to group together the material effects [of the power of the stars] under the aegis of the four Elements which are supposed to compose the world at the time: Fire, Earth, Water and Air. Admittedly, Ptolemy did not invent these Elements, but he transposed them for the first time into the field of astrology.” This monumental and astounding blunder by this otherwise very talented translator demonstrates by the absurd how even the most informed minds are preconditioned to believe that the Elements are consubstantial with astrology…

As its name suggests, the Tetrabiblos is composed of four books, each dealing with a particular aspect of astrology. Ptolemy’s lively yet stripped-down style is very well rendered by a fluent translation. But if he writes in a simple language, it is not always easy to follow as his way of thinking and rationalizing is often foreign to that of a 21st-century reader. It must be read with extreme analytical attention to succeed in deciphering the very real unity of some of its underlying theories.

Book I: The Principles of Astrology, Theory and Practice. Ptolemy exposes the foundations of astrology according to tradition and according to his own conceptions. It is exclusively on this first book, unless otherwise stated, that I based myself to produce this series of four video animations, systematically favoring the personal theories of Ptolemy.

Book II: World astrology and universal charts: predictions by eclipses, comets and other celestial phenomena. Ptolemy exposes traditional beliefs as well as his own general and forecasting conceptions in terms of collective astrology, astro-meteorology and geographical astro-anthropology.

Book III: Individual Birth Charts: Predictions of Birth, Lifespan, Body and Temperament, Diseases, and Soul Characteristics. Ptolemy exposes there the traditional beliefs as well as his own general and forecasting conceptions in the matter of individual astrology.

Book IV: Individual Birth Charts: Predictions regarding wealth, family, friends, travel, type of death, and life ages. It is in fact an extension of Book III, but more focused on forecasting and its various methods (transits, primary directions, etc.). I have retained only the section devoted to the ages of life, since it has a direct and organic relationship with the theories presented in Book I.

It takes a trained eye and a good knowledge of astrology and its history to be able to distinguish texts of an encyclopedic nature, which present traditional elements that Ptolemy exposes without necessarily approving them, texts where he proposes its original and innovative designs. And even in this case, it is not always easy as the two are mixed together and as Ptolemy seems both to be one with the tradition and to want to stand out from it. Sometimes even the reference to “old” accompanies proposals that have nothing to do with the past, as if he were thus trying not to cut himself too much from tradition by dint of innovative boldness.

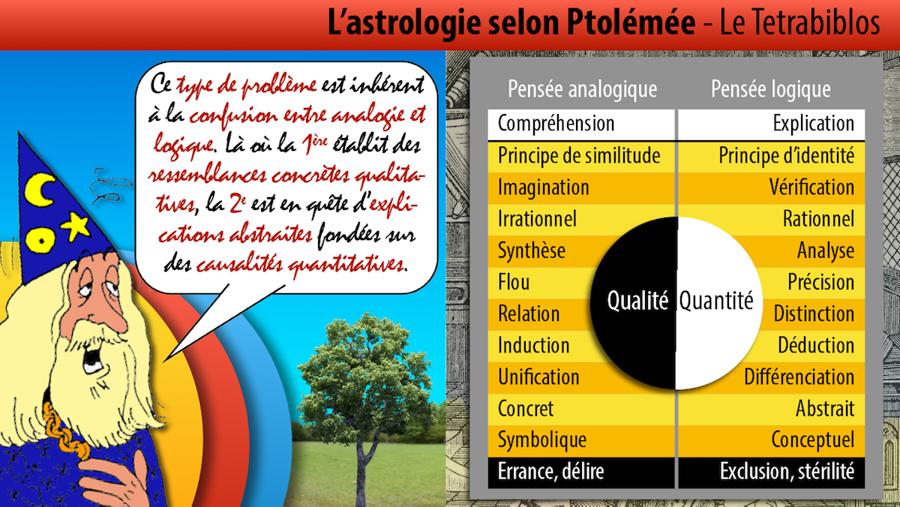

In another register, the authentically scientific character of Ptolemy’s approach is beyond doubt. Within the limits of the knowledge of his time, he strives to push as far as possible a rational and causal explanation of astrology, which he considers to be neither more nor less a natural science that he connects with others. But his rationality is not ours. Its logic, real and rigorous, is exercised within a cognitive framework characterized by the analogical thinking which was then dominant. The principle of identity, proper to logical thought, coexists in him with the principle of similarity which characterizes analogical thought. Concepts and symbols intertwine in weaves that often produce disconcerting paralogisms.

This juxtaposition and intertwining between rational and irrational, vagueness and precision, quantitative and qualitative, induction and deduction, causal explanation and intuitive understanding are not unique to Ptolemy’s personal thought. They also characterize that of all the thinkers and scholars of his time and of the centuries that preceded and followed it until the 17th century: we find for example the same amalgams in Aristotle or in Kepler. We are in the presence of a differentiating thought that seeks its way within a conception of cosmic nature with organic unity where everything is held together, where each element echoes all the others, where “everything above is like below” and vice versa. This can obviously lead to wanderings and to what modern thought, with a rationality that wants to be definitively accomplished, can consider, often rightly, as delusions of interpretation where the ancient thinker only follows the Ariadne’s thread of a reason that stubbornly seeks itself in a “symbol forest” (Baudelaire). But modern rationalists, whose reasoning is too often marked by the exclusions and sterility of a fragmented and desiccated conception of the world, should remember that it is from this strange alembic that modern thought sprang and from which all contemporary sciences have come.

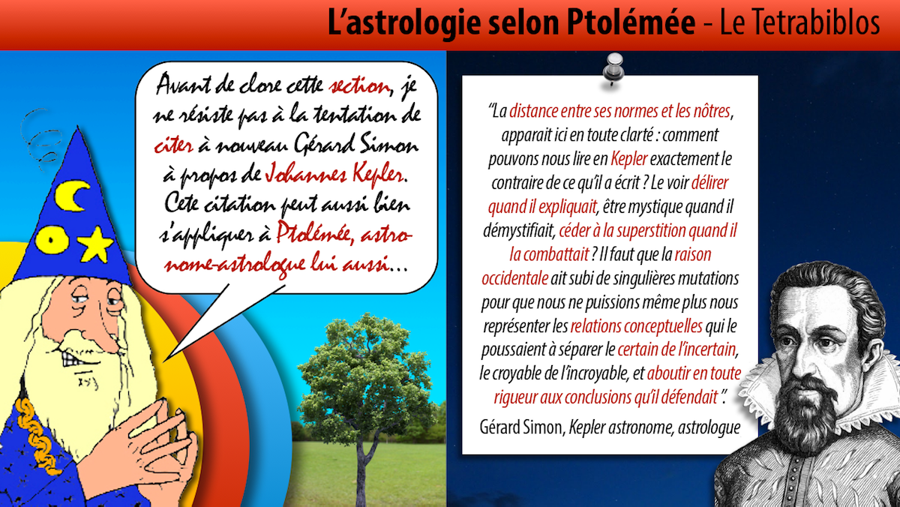

We indeed find the same type of thought 14 centuries later in Johannes Kepler, founder of modern heliocentric astronomy. Like Ptolemy, he was at the same time an astronomer and an astrologer. Certainly, in about 1400 years, logical thought has made further progress in the maquis of analogisms, but we remain globally in the same cognitive framework. If he were not fertile, if the irrational had not irrigated the rational, Kepler would not have been able to discover and state the astrophysical laws that bear his name.

From this point of view, what writes about Kepler science historian Gérard Simon (1931–2009) also applies to Ptolemy: “The distance between his standards and ours becomes clear here: how can we read Kepler exactly the opposite of what he wrote? See him raving when he explained, be mystical when he demystified, give in to superstition when he fought it? Western reason must have undergone singular mutations so that we can no longer even represent to ourselves the conceptual relations which drove it to separate the certain from the uncertain, the believable from the unbelievable, and arrive in all rigor at the conclusions that he was defending” (Gerard Simon, Kepler astronome, astrologue, Gallimard 1979).

To read and understand Ptolemy well, we must therefore be careful not to give in to retrospective anachronisms of a triumphant modern reason that has too much of a tendency to gauge and judge rationalities prior to its own by the yardstick of its own, as if it were not its heir, product, fruit, descent. This avoids making gross misinterpretations and errors of epistemological diagnoses because, as Gérard Simon writes very well about Kepler, “Even if he criticized the credulity of his contemporaries and the arbitrariness of the astrologers of his time, he never questioned the validity of the possibility of drawing predictions from the movement of the stars. Quite the contrary, he endeavored to specify their theoretical foundations, and he treats simultaneously and on a plane of equivalent dignity astronomical problems and astrological problems.”

A considerable part of the Tetrabiblos is indeed dedicated to individual or collective predictive astrology. It is even one of the main subjects of his introduction. Ptolemy carefully distinguishes the aptitude of genethliac astrology to make prognoses relating to the temperament, the character, the human psychological characteristics in relation to the configuration of the sky of birth, of that consisting in foresee or predict events subsequent to this, based on planetary cycles that are very often real (transits) and too often fictitious (directions, progressions).

For an anti-astrology scientist, the two types of prognosis are to be put in the same bag, since he denies astrology any predictive possibility, whether it relates to innate temperament or post-natal deadlines. But for a modern astrologer, the importance that Ptolemy gives to predictive astrology, that is to say, not relative to the birth chart, seems exaggerated, excessively deterministic and far too focused on prognoses of future events.

Indeed, over the centuries it has come to appear (at least to learned, observant, rational and experienced astrologers) that the astrological forecast itself did not concern the event prognosis. For these knowledgeable astrologers, the forecast — not prediction — relates only to trends, temperamental climates induced by post-natal planetary cycles and intercycles, in agreement or disagreement with the configuration of the birth sky. From this modern point of view, it is the reaction adapted or not with which the individual will react to these tendencies, taking into account his natal sky and according to the other extra-astrological parameters which determine him, which will be productive or not of events of which planetary influences will be partially the cause. The individual is in fact constantly confronted with a multitude of random events and situations, foreseeable or not, which originate elsewhere than in the course of the planets and which nevertheless determine him. Thus, we can say that if there is a fatality, it is much more terrestrial (geographical, genetic, socio-cultural, economic, etc.) than celestial.

But if Ptolemy was careful to underline the conditional, relative character of any astrological prognosis, his conditionalism and his displayed relativism may seem overly deterministic to a modern mind. This appears clearly in the last three books of the Tetrabiblos, where he develops and illustrates the theoretical and practical principles that he merely exposes and explains in the first. To read it, one could believe that everything seems written in the natal horoscope of an individual: not only his innate temperament, but also his morphology, his predispositions to good health or diseases and even to what types of pathologies he will be exposed, the type of job he will be called upon to exercise, his family relationships, etc.

Since it is here a question of individual horoscope and therefore of hour of birth, I take this opportunity to rectify a gross lie uttered by Henri Broch, biophysicist and pseudo-zetetician who doubts nothing when it comes to indulging in his hobbies, the most obtuse scientistic anti-astrologism. In the chapter devoted to astrology of his book Au cœur de l’extraordinaire (Book-e-Book, ed. Zetetic), this very ordinary disinformator writes that “to build a horoscope, Ptolemy recommends… the date of conception rather than the date of birth”. This is completely false. Either Broch has not read Ptolemy, and in this case he is talking nonsense. Or else he has read it, and then he is knowingly lying.

Here is exactly what Ptolemy writes on this subject in Book III: “The chronological starting-point of man is by nature the moment when conception takes place, but, potentially and necessarily, it is the moment of birth […]. We could call conception the genesis of the human seed, and birth the beginning of man, […] a point of departure potentially equal and even more important than the preceding one.” Contrary to what Broch writes, Ptolemy draws a clear distinction between the time of the design and that of the birth, and written in full that the second is more important than the first. Regarding the conception horoscope, it is even more precise about the information that can possibly be drawn from it: “But if we want to establish a more in-depth examination of the characteristics that occur at the time of design, the examination of these properties, carried out with the same reasoning, will only contribute to the knowledge of the only properties of the combination itself. even.” Which means without any ambiguity, translated into contemporary language, that the design chart would only give information about embryogenesis and fetal life.

Now let’s come back to the information that can be drawn from a natal chart. It is absolutely obvious to any rational and experienced practicing astrologer that all the data that Ptolemy thinks he can extract from the individual horoscope can in no way be deduced and extracted from the study of the natal sky of an individual, and therefore cannot be the subject of any forecast and even less of predictions.

Here again comes into play this fundamental characteristic of ancient analogical and unitary thought, for which it is difficult to differentiate a predictable trend events, foreseeable or not, of which she is likely to give birth. And here also comes another parameter: in the essentially agricultural societies that were those of antiquity, it was absolutely vital to be able to foresee and even if possible to predict precisely what the future climatic and meteorological conditions would be. Agriculture abhors the uncertainties of the future and seeks to protect itself from them: nothing could be more logical and fundamentally natural. This is one of the almost reasonable reasons why astrology and meteorology have been coupled for millennia, even though it was a error. If we associate this “agricultural thought” With analogical thinking, we understand that the distinction between forecasting (prognosis of a strong future probability) and prediction (prognosis of future certainty) was very blurred among the ancients, scholars or not.

Ptolemy therefore had some excuses. Of course, he also granted astrological forecasting a philosophical, moral and consoling dimension by writing that “Knowledge of the future accustoms and soothes the soul by preparing it to accept the future as if it were present, and leads it to welcome any event whatsoever with calm and serenity”. But the fact remains that he also granted astrological forecasting much more than she is actually capable of. And what is valid for genethliacal, individual astrology (Book III of the Tetrabiblos) is also valid for global, collective astrology (Book II), where its forecasting techniques based, in addition to real and/or imaginary planetary cycles and intercycles, on eclipses and the passages of comets, appear as pure delusions — this that they actually are. It is the same when he strives, in Book IV, to want to predict or predict the date of death using techniques that are both rational in their procedures and irrational in their finality, since he is impossible to predict this date from a natal chart.

By reading and rereading the Tetrabiblos with the eyes of an informed astrologer rather than those of a Hellenist, a pseudo-traditional astrologer or an obsessive anti-astrology, it is not very difficult to see that Ptolemy was above all a theorist of astrology, of which it is probable that his practice was very limited.

To see and understand this, we must remember once again that the Tetrabiblos is both a compilation of astrological knowledge from the past and an exposition of the personal and very original theories of Ptolemy. It is therefore essential to know how to distinguish them, which is not within the reach of the first comer.

It is easy to spot Ptolemy’s personal and original theories: they are always based on precise astronomical data which are in a way the “brand” of the scientist since they are only found in the Tetrabiblos and in no earlier or contemporary astrological writing.

To define and justify the planetary properties and influences, it refers to the order of the distances of the planets from the Earth coordinated with the rational and dosed combination of the 4 Qualities Hot, Wet, Cold and Dry. To define and justify the zodiacal properties and influences, it refers to the concrete and real diurnal-nocturnal cycle of seasonal and daily variations induced by the intertropical declinations of the Sun around the equator in the ecliptic plane, coordinated with the diurnal-nocturnal duality abstract and symbolic when it comes to justifying the alternation of Signs.

Once equipped with this Ptolemaic compass, it is relatively easy to find one’s way in the compiling maquis that is also the Tetrabiblos. When Ptolemy plays the encyclopaedist and then exposes traditional practices, beliefs, dogmas or theories that predate his own conceptions, in most cases he announces the color by a phrase in the preamble like “The elders say that…” or “Tradition says that…” or, more vaguely, “We say that…”

Death phrases marking a distance from what he is going to exhibit, one can never explicitly infer that he approves or disapproves of it. Ptolemy is not a polemicist. In any case, he strives to rationalize these propositions — which is also his trademark — by endowing them with an external astronomical logic if he can, or an internal logic of his own if it is. is impossible, which is frequently the case. He can thus embark on very long rationalizing presentations in an attempt to find, at all costs, an internal logic to proposals which seem apparently devoid of it and which are very far from his own conceptions. And that, it seems, for the sheer pleasure of rationalizing and logicalizing what he exposes.

This mode of intellectual functioning is also exercised in the techniques of interpretation that it both exposes and proposes. He never seems to question their relevance and does not explicitly reject any of them, not even the most delirious, absurd and above all deterministic ones when they can be contradictory with his conditional and relativistic conception of zodiaco-planetary influences. But he seems to take immense pleasure in systematically applying a sort of abstract set theory which gives them a powerful internal organization which he gives the impression that it is sufficient in itself. And in doing so, it seems at the same time quite indifferent to the concrete practices on which this abstract theorization necessarily leads.

All this therefore suggests that Ptolemy cared very little about astrological practice and even that if he practiced, he only did it occasionally and episodically. This experience in the field would probably have led him to sort out his compilatory and contradictory presentations.

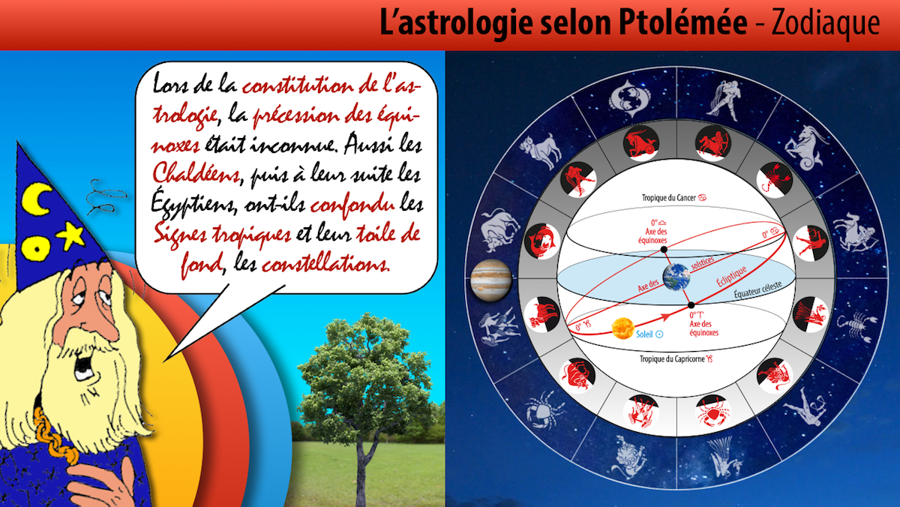

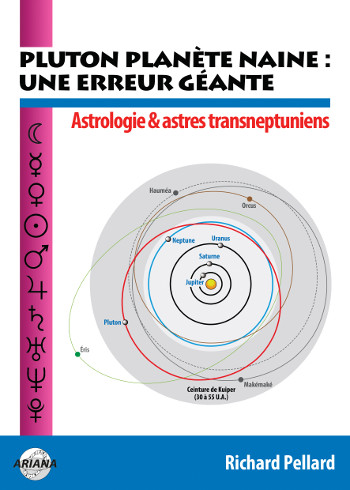

One of the problems with the Tetrabiblos is that of the real position of Ptolemy vis-à-vis the constellations zodiac. He is, as an astronomer, a determined disciple and successor of the astronomer Hipparchus of Nicaea, who is probably the one who discovered in – 2nd century the mechanism of the precession of the equinoxes. This mechanism explains why the groups of stars in the background of the ecliptic and therefore of the zodiac make a total apparent rotation approximately every 25,760 years, which induces that every approximately 2147 years, the stellar decor (the constellations) changes behind each section of the apparent geocentric course of the stars on or near the ecliptic between the tropics (the Signs).

It was following the discovery of Hipparchus that scholars distinguished the tropical year, the time interval separating two vernal equinoxes, and the sidereal year, the time interval at the end of which the stars and the Sun return to their identical previous relative positions.

The zodiac as Ptolemy conceives and explains it very clearly is not that of the constellations (sidereal zodiac) but that of the Signs (tropical zodiac). We can even affirm that he is one of the very few astrologers of his time, and even of the centuries since the discovery of Hipparchus, to consider, and rightly so, that the true zodiac is the tropics.

From this point of view Pascal Charvet, the translator of the edition of the Tetrabiblos to which we refer here, makes a gross error by writing in its introduction that “To avoid this continual discrepancy between the Signs of the zodiac and the zodiac constellations, Ptolemy detaches from this zodiac of constellations (or sidereal zodiac) a ‘fictitious’ zodiac which he moors at the point of the spring equinox, in the cosmic march which rotates the earth’s axis […]. This zodiac of the Signs, insensitive to the precession of the equinoxes, is independent of the constellations: like the constellations, the Signs will no longer draw their name directly from mythological stories, as we read in Eratosthenes, but from the characteristics of temporal cycles and especially seasons.”

Indeed, the zodiac to which Ptolemy refers has nothing “fictional”. It is on the contrary the real zodiac, because no other astronomical reality can justify the existence of the zodiac except that of the intertropical declinations which is at the origin of the cycle of variation in duration of the diurnal and nocturnal arcs of the Planets (days and nights for the Sun), the constellations in the background being only the stellar decoration of this cycle which originates in the rotation of the Earth on its axis inclined on its orbital plane.

But it is true that Pascal Charvet was advised by an astronomer (and these are generally anti-astrology) and that he himself has a vision of astrology that is more poetic than technical: “By stripping the astrological zodiac of its rich mythological substance”, he writes in his introduction, “the scientist undoubtedly impoverishes it, but by inscribing it in the deep rhythms of the universe, he gives it both a permanence independent of all cultures and a constantly renewed fruitfulness.” Such impoverishments are demanded every day!

Ptolemy is certainly an enlightened defender of the tropical zodiac of the Signs specific to the inclination of the Earth in its orbit against the sidereal zodiac of the constellations. But he nevertheless proposes, in Book I of the Tetrabible, a catalog of stars and constellations, to which he grants a certain influence, which he compares moreover to that of the Planets and not to that of the Signs, which is very significant, and which he does not however manage to explain and justify. He even uses the zodiac of the constellations on the sly to also try to explain and justify the ancient and absurd doctrine of the Planetary Masteries over the Signs. I will not dwell at length on the reasons for these flagrant contradictions, since they are illustrated in the fourth episode of the video animations devoted to this subject and that, to paraphrase Napoleon Bonaparte, “a good sketch, especially if animated, is better than a long speech”.

Let us only note that Ptolemy never tries to explain the influence that he still wants to attribute to the constellations by astronomical considerations in relation to the declinations or relating to the 4 elementary Qualities. It is a… sign (!) that does not deceive, especially since in its personal, natural and rational explanation of the tropical zodiac, it never mentions the sidereal zodiac.

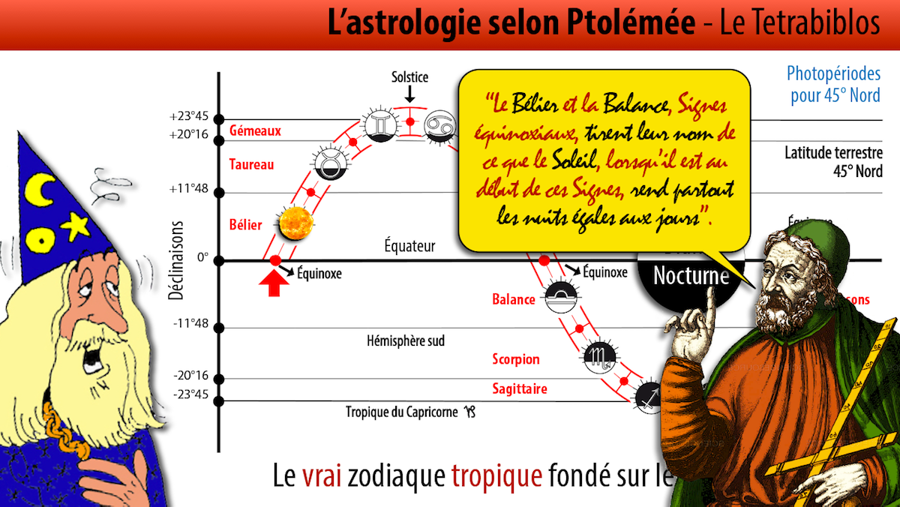

Thus, in the section of Book I devoted to the zodiac, Ptolemy writes that “Aries and Libra, equinoctial Signs, take their name from the fact that the Sun, when it is at the beginning of these Signs, makes everywhere the nights equal to the days”, thus clearly referring to the tropical zodiac as the natural basis of his conception of the Signs.

On the other hand, it is at the end of the section of this same Book devoted to the Planets that he evokes the zodiacal constellations, but also certain stars located to the north or to the south of these (therefore outside the zodiacal band surrounding the ecliptic), as a preamble to a catalog of stars also appearing in the Almagest, his treatise on astronomy. It will therefore be noted, and this is very important and significant, that Ptolemy decided to situate the role and influence attributed to the stellar sphere in the section “Planets” and not in the section “Zodiac”. Since all of his talks are very neat and organized, this cannot be a misclassification.

He begins the presentation of this catalog thus: “As fixed stars should be treated according to the nature of the effects they produce, […] here are the characteristics observed in them according to the mode followed for the nature of the Planets. We will start with the stars that occupy the figures located all around the ecliptic circle.” And at the end of the catalog he writes the following sentence: “Here, then, are the individual powers of the fixed stars according to the observations made by my predecessors.”

The introductory and concluding formulations of this stellar catalog refer us to an already mentioned characteristic of Ptolemy’s style when he plays the encyclopaedist and exposes traditions that he relates honestly without necessarily adhering to them, and that he subtly indicates it by using certain phrases suggesting distancing. Here, the beginning of the introductory sentence and the end of the concluding sentence, “How to treat…” and “…observations made by my predecessors” are obviously part of the same type of stylistic twist.

Always very careful and thoughtful, Ptolemy even took an extra precaution. In the presentation of this stellar catalog, if it expressly refers to the zodiacal constellations, he is careful not to attribute to each of them a global meaning, property or influence as such. The case of each star or group of stars belonging to the same zodiacal constellation or located outside the zodiacal band is thus treated in isolation, depending on their positions at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of this constellation.